A Scoop of History on the Lower East Side

Bestselling author Susan Jane Gilman on Frank McCourt, Italian immigrants, and the Upper West Side

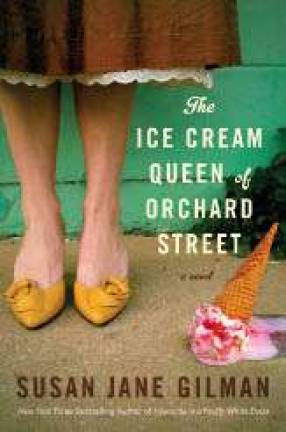

Susan Jane Gilman has skillfully combined ice cream, New York, and history all into one novel. In "The Ice Cream Queen of Orchard Street," readers follow a young Russian immigrant who moves to the Lower East Side with her family, only to get crippled by an ices peddler shortly after her arrival. The man, who is an Italian immigrant, takes in the girl out of guilt, and teaches her his trade.

Set in 1913, the novel takes us on a 70-year journey through history, reminding us of all the hardships New Yorkers overcame in that period. Telling the story through an underlying theme of ice cream was an easy choice for the author. Although a seemingly simple subject, ice cream has a rich and complex history, one that Gilman embraced. "I was interested in it intellectually and then I just love to eat it," she said.

On your website, you describe yourself as "made, born and raised in Manhattan." Which neighborhood did you grow up in?

I grew up on the Upper West Side before it was the neighborhood as we know it to be today. I watched a lot of it get built -- the high rises, the luxury condos. But then, it was still pretty rough and tumble and dangerous. I was made in Lincoln Towers on 69th Street and West End Avenue. When I was born, we lived on 96th between Amsterdam and Columbus. I used to take the subway to school when I was in junior high and high school and you really had to plan what streets you walked down to get to Broadway or to a friend you were going to visit. My friend's parents would make her call when she got to my house, and she just lived a block and a half away. It was really dicey. My brother used to get beaten up, our neighbor was shot. When I grew up in New York, you were just always on guard -- you learned how to walk and how to try to look tough.

You dedicated this book to Frank McCourt, who was your teacher at Stuyvesant. That's so cool.

It's really cool. I miss him. He was not just my teacher, but he really influenced me. He was the person who encouraged me to be a writer; he told me to send a piece I'd written to the Village Voice. And I was 16 years old and I did and they published me. And it was the first time I was ever published. And that was Frank McCourt. I promised myself that whenever I wrote a novel, I would dedicate it to Frank McCourt; this was before he wrote Angela's Ashes. I thought, "I'll dedicate it to my teacher so he's remembered too." [Laughs] And he and I stayed friends until the day he died. When my second book made the New York Times bestseller list, he was the first person I called.

What was your first published piece on?

My father came to New York from Italy, so I was happy that you wrote about Italian immigrants. Why did you make that choice?

I chose that for several reasons. The reason that Italians feature so prominently is because, in my mind, Italian immigrants at the turn of the last century were like the prophets of ice cream. Especially the Sicilians and the Neapolitans. They brought recipes with them. They started the ices trade. There's a guy, Italo Marchiony, who was credited with creating the precursor to the ice cream cone. And that was a big business. Also, Italians were the ones who were sharing the Lower East Side with the Jews. And as a novelist, I wanted my protagonist to grow up in a family that was unlike her own. Also, I always have an impulse as a writer to explode stereotypes. I didn't want to write a nice, sweet ice cream woman. I wanted to write a really complicated, sort of nasty female antihero because women aren't portrayed like that. Also, Italians, I think, sometimes get a raw deal in the media, with either "The Sopranos," with the Mafia or everyone slapping each other upside the head and yelling, "Mom, make the sauce." Italian Americans disproportionately served in both wars, World War I and II, they built huge infrastructure, they gained so much, and nobody writes about that.

How did the ice cream idea come about?

Because I just love ice cream. If you're going to write a novel, even with my nonfiction, it's like asking it to move in with you for several years. And you're not gonna love it every moment, sometimes you're going to hate it and hate yourself. It's like living with a lover. So you have to make sure that you really in love with it. So in moments where you hate it and hate yourself, it will really sustain you.

What are some historical facts you can tell us about it?

Prohibition was great for ice cream because all these taverns and bars had to turn themselves into ice cream parlors to make money. In World War II, the U.S. government became the largest ice cream manufacturer in the world because they were supplying ice creams to the troops.

I read that part of your research for the book involved you working at a Carvel on Long Island.

Yes, I was very much inspired by Tom Carvel's story. That's why I originally got the idea. I learned that his real name was Tom Carvelas; he was a Greek immigrant. And he came over to the States with nothing. I loved Carvel as a kid. So I contacted the Carvel corporation and I told them I was writing a novel, and asked if there was a Carvel somewhere near New York City where I could go and visit. And they hooked me up with this owner named Zaya Givargidze, out in Massapequa Park. I said, "Could I work here for a day or two?" and he said, "Sure." And he taught me the trade and I got to make a Fudgie the Whale cake.

For more about Susan and her books, visit www.susanjanegilman.com.