One of Many

Elderly homeless woman attracts support networkon the Upper West Side

Esther doesn't like to be called homeless, because, she says, she has a room in the Goddard Houses on West 87th Street. Right now she lives in front of a coffee shop at 76th and Broadway, in a shelter she made of boxes and plastic sheeting.

She's dressed in a long black coat and a brown ankle skirt with a red scarf tied around her neck. Her fingers are bent at right angles and don't work properly in the cold. On her head is a black straw hat with the brim cocked down to hide her eyes. On her right wrist is a "fall risk" bracelet she received during a recent hospital visit for an unspecified ailment.

Esther is a kind, intelligent and proud woman who talks fondly of books and of people she's befriended on the street. She uses words like "didactic" and is against staying in a homeless shelter because she feels unsafe there.

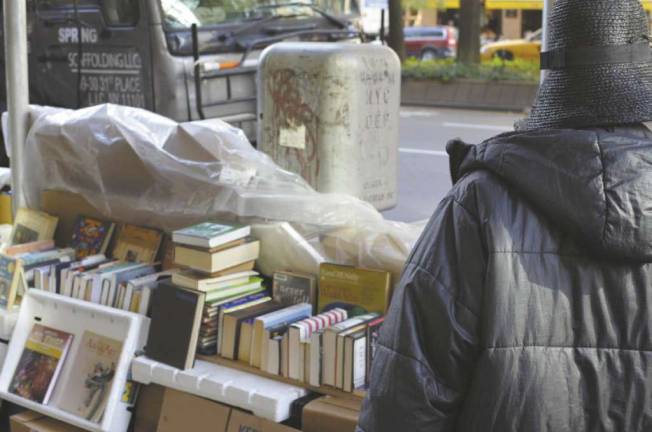

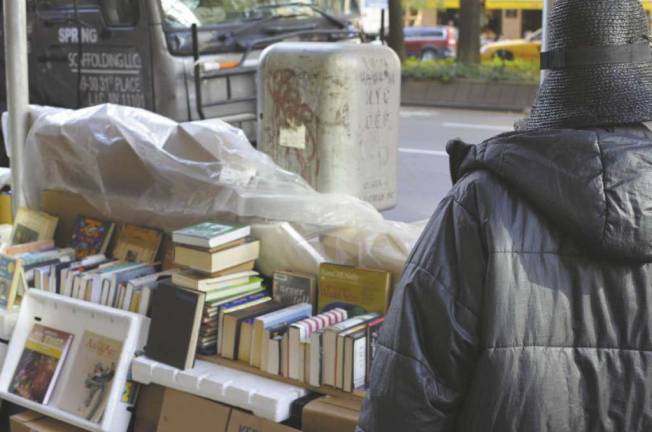

For money and something to do she sells second-hand books to passers-by. Amid titles by popular authors - Patterson, Evanovich, Sedaris - are economics textbooks, an atlas, a film guide from 1995 and a copy of "Dr. Neruda's Cure for Evil" that was donated by her friend Mimi, who lives nearby.

The fact that Esther has non-homeless friends - who visit her often, bring her books to sell and tips on nearby programs for the homeless, and watch her things while she goes to the bathroom - is one thing that sets her apart from the majority of homeless in the city. She is also in her early seventies - part of a rising population of elderly homeless people in the city.

"I care about her as a person," said Blair Sorrel, another Upper West Sider who is friends with Esther. "It's just compassion, I don't want any harm to come to her, what happened is beyond her control."

Esther is in a legal dispute with the Goddard Houses over her eviction in June, the details of which are unclear. What's known is that a judge has yet to decide whether her eviction was legal, and Esther has a hard time finding information out about her case. She collects money from Social Security, but says she's on the bottom end of what a person can earn.

Regardless of her legal issues, she knows colder weather is coming and that she can't stay here. She's also aware of the possibility that city authorities will forcibly remove her from the streets for her own safety once temperatures drop.

Sorrel said it's hard to influence Esther to go into a shelter or otherwise seek help because she sometimes has a tenuous grasp on reality and is occasionally forgetful, like when she mistakenly recognizes people walking past her outpost or misplaces important papers. Her friends understand Esther's fear of shelters, where she could have to contend with unruly drug addicts and the mentally unstable, but the reality for her and others like her is that she faces many of the same dangers out on the street, plus the coming cold.

According to the Coalition for the Homeless, NYC's homeless population is over 50,000 people, including 12,000 families and 21,000 children. During the winter months many shelters and programs face overcrowding.

Unlike many, Esther does not lack for benefactors. During conversations with a reporter over a couple days, two people drop a bag of books off for her and four others stop by to either help clean up or to offer information on local programs or cheap apartments. A regular named Barbara implores Esther to take advantage of free legal advice that's available on Tuesdays at the Fourth Universalist Society on West 76th Street. Mimi helps Esther straighten up her book store so a photo can be taken that comports with her standards.

According to Esther and her friends she has several high-level degrees, but declines to be specific because "it's too humiliating." Esther insisted the West Side Spirit use a pseudonym and declined to be in photos where her face is seen.

"She's clearly intelligent, she notices when a book is missing," says Sorrel by way of example. "It's hubris to think [homelessness] couldn't happen to anyone. Especially in this economy, everyone is suffering."

Mimi considers Esther her friend, and says she gives back to the community by befriending older and isolated people who visit just to enjoy Esther's company and conversation. Indeed, a very elderly woman stops by one recent Monday to give Esther an advertisement for apartments at $125/week, which Esther says is affordable.

"I'll give them a call," says Esther. "Thank you my darling!"

Esther also enjoys the kindness of a few nearby businesses: the Starbucks across Broadway gives her so much food she winds up giving a lot of it away. The cafe on the corner allows her to use the bathroom whenever she wants and some of the employees of the West End Market - which is open 24 hours a day and is a major reason Esther chose this spot to live - also look out for her. Some of the businesses are put off by her presence and file complaints with city agencies, but Esther has people like Mimi who write letters to those businesses supporting Esther.

"Her kindness," says Mimi, when asked why she cares about Esther. "She's very spiritual and very funny." Mimi and others have alerted local leaders to her plight, but run into a roadblock because Esther doesn't like to give out her social security number and photo ID in order to get into a shelter or take advantage of another form of help.

"I need to get into a home, not a shelter," said Esther. "I need somebody to step in."