The Art of Regret

Jasper Johns' recent works at the Museum of Modern Art

Summer pleasures are plentiful, but the Museum of Modern Art is providing an unexpected one in a relatively small, but impressive exhibition of an American master. Catch it in its last remaining days.

Jasper Johns: Regrets, on view through September 1, gives viewers a chance to revisit, rethink and re-engage with an iconic artist. Johns is still creating vibrant, thoughtful new work in his 84th year, and this powerful collection gives an intriguing view of the artist's process.

Two galleries in the museum, introduced by a recent photograph of Johns, hard at work, are filled with two large paintings, 10 complex drawings, and two prints, each presented in a variety of states. One of the prints was completed in over 15 states. All of the work in the show was created over the last year and a half. A case holds two of the artist's working copper plates, which also offer a rare perspective on the process.

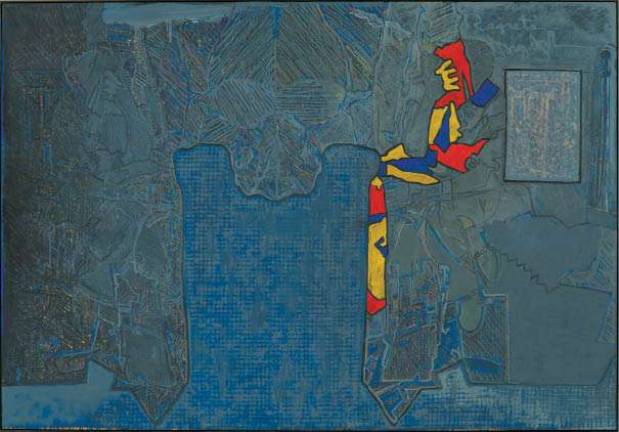

The large-scale paintings, abstractions in blues and greys with horizontal and diagonal lines and bands, are offset by bright shapes popping out in primary colors. A densely worked and mysterious watercolor painting echoes some of the same shapes, but with an entirely distinct feeling. A face seems to hover just past recognition. A rectangle is framed, but it's not clear what it's meant to frame.

Even non-representational art represents something. Conceptual art represents a concept. Time-based art represents a process. Jasper Johns's work often re-presents representations. Numbers stand for quantities. Maps depict locations. Flags represent political entities. Johns' work includes numbers, but without telling what's being counted. It includes maps and flags, but doesn't provide a key for deciphering them. His iconography is personal and enigmatic.

Curators Ann Temkin and Christophe Cherix, who worked with Johns on the exhibition, provide clues as to how to approach these works. Johns, they tell us, encountered a photograph in a catalogue that caught his eye. It was worn and damaged, and depicted the artist, Lucien Freud, sitting with his head down, his hand holding his forehead. Johns responded to the photograph's compositional elements as well as its emotional resonances in fascinating ways.

The figure, once pointed out, can be perceived in the works, but only with difficulty. Complex lines and brushstrokes obscure the outline; monochromatic tones further the effect. An area of damage in the photograph replaces the figure as the central element. But, without the crucial keys provided by the curators, the shape is just a silhouette of an unknown form.

Regrets, the title of the exhibition, is derived from a stamp that Johns had produced some years ago. Constantly receiving requests and invitations of all kinds, from all over, he found it expedient to just return them stamped with the response, "Regrets, Jasper Johns." It's hard to imagine that the downward facing pose of an artist, bowing with his head in his hands didn't suggest another form of regrets. But that's a key that was not given.

Jasper Johns' stature in the art world is hard to overstate. Major museums include him in their permanent collections, and regularly display important pieces along with the work of other modern masters. But, often, one will encounter a few pieces. Great works, but not in great number. The thoughtfully composed selections in Regrets give audiences the chance to consider a significant number of cohesive, recent works.

Curator Cherix said, previewing the exhibition, that the museum hoped "to give the viewer the opportunity to understand not only a new body of work, but how this body of work was developed. From one drawing to a painting to a print, again to a painting, and then again to a print, and so on," which, he added, is "something which is very typical of Jasper Johns' work."

In the exhibition, imagery echoes across media. Watercolor and oil express related thoughts in very different ways. Visual and conceptual densities are achieved by working and reworking the same motifs. It's a fascinating glimpse in to the way a highly evolved artist works things out to his final satisfaction.

We are given the chance to consider the personal iconography Johns has developed and through which his art speaks. The works hold symbols that are obvious-numbers or figures-which become mysterious as they are obscured, painted over, scratched out or buried. When the everyday, recognizable qualities of things are removed or replaced, when the obvious now holds mysteries, art has taken place.