The Backstory of a New York Story

The New-York Historical Society celebrates Madeline's 75th birthday

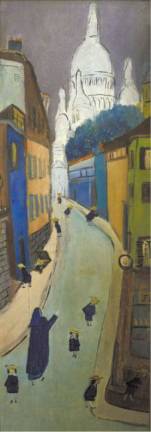

In a show replete with surprising historical detail, one fact rises to the top. The much-loved tale of a Parisian schoolgirl, in yellow hat and bright blue coat, was written and published in New York. Specifically, the opener was scribbled on the back of a menu in Pete's Tavern on Irving Place, near Gramercy Park.

Its author-artist-writer-hotelier-restaurateur Ludwig Bemelmans (1898-1962)-was a New York transplant, having come here from Europe as a teenager. Of Belgian-German ancestry, he was a bad boy who dropped out of school at age 12 and apprenticed in the family hotel business in the Tyrolean Alps before he was dismissed after supposedly shooting a waiter.

He came to New York in 1914 and took a job as a busboy at the Ritz-Carlton on Madison and 46th Street, where he worked for 15 years. He loved the people and the buzz, so much so that he produced a series of self-referential illustrations for Town & Country ("Adieu to the Old Ritz") that was published shortly before the old hotel was demolished in 1951.

That series and some 100 other paintings, drawings, books, artifacts and memorabilia, including specially commissioned panels for the playroom of Aristotle Onassis's yacht "The Christina," are on display at the New-York Historical Society in Madeline in New York: The Art of Ludwig Bemelmans, now through October 19, 2014.

Organized by the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in Amherst, Mass., the exhibit owes a debt to N-YHS trustee Charles Royce and his wife, Deborah, who lent murals rescued from a Parisian bistro, La Colombe, once owned by Bemelmans. The murals were put on display at The Ocean House, their hotel in Watch Hill, Rhode Island-a little-known rival to Bemelmans Bar at The Carlyle hotel on the Upper East Side, which boasts walls covered with scenes the artist painted of Central Park and Madeline-themed lampshades. (The bar also serves a cocktail, "The Ludwig," in honor of its muralist, who lived rent-free with his family at the hotel for 18 months in exchange for his services.)

Bemelmans was nothing if not productive once he found his métier in New York. He was a cartoonist for The New York World in the early part of his career and went on to illustrate more than 30 covers for The New Yorker (plus matchbooks for now-defunct Luchow's on 14th Street). He wrote plays, screenplays, magazine articles, and books for both children and adults, including six in the Madeline series.

He famously drew on everything in his path-napkins, menus, hotel stationery, note cards, even the walls of the kitchen at the Ritz. When Viking Press editor May Massee came to dinner and saw the drawings on the shades in his 8th Street studio, she declared, "You must write children's books!"

Indeed the germ of the idea can be traced back to childhood memories of his mother's convent school in Bavaria and his own boarding school (like Madeline, he was "the smallest one"). In the summer of 1938 Bemelmans suffered a traumatic experience when he was knocked down by a baker's van while he was cycling on the Ile d'Yeu, off the coast of France. Gazing at the ceiling from his hospital bed, he discerned a crack that looked like a rabbit. A young girl who had just had her appendix removed proudly displayed her scar.

Back in New York, he took these experiences, along with a debut drawing of our heroine from his children's novel The Golden Basket (1936), and folded them into Madeline, published by Simon & Schuster on September 5, 1939, just days after World War II began.

Fans will thrill to the sight of the artist's paint box, the original manuscript for Madeline, the dummy cover for Madeline and the Bad Hat, and the brown chapeau with red pom-poms that inspired the one worn by the Bad Hat himself, Pepito, the son of the Spanish Ambassador.

Children's book author Maira Kalman worshipped Ludwig Bemelmans. He was her hero. So it is fitting that her four-part illustrated tribute ("Dear Ludwig Bemelmans," 2014) serves as the exhibit's coda. A mash note, it concludes with a scene at Bemelmans Bar-the Steinway, the waiter with a tray of martini glasses, the posh clientele, and of course the murals. "You are with us, truly. L.B. you cannot return. But we don our hats and salute you. Yours, M.K."