The Civil War Revisited on the Upper West Side

Historian and author Thomas Fleming captures the struggles that led to the Civil War

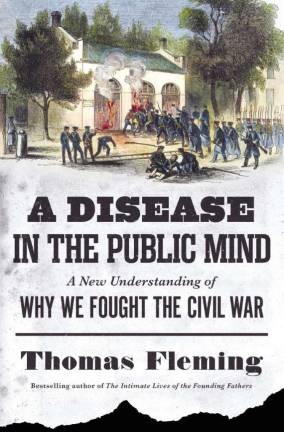

More soldiers died in the Civil War than in all previous and past wars combined. This staggering fact opens Thomas Fleming's book A Disease in the Public Mind: A New Understanding of Why We Fought the Civil War. The Upper West Side historian and frequent guest on PBS and the History Channel devoted himself to unearthing the reasons this war really started and what led up to it. This disease he refers to is the misconception that people had at the time that blacks were not equal to whites. "The public mind is how you see the political and religious world of your time. And when these basic beliefs get scrambled in people's heads, then you got trouble," Fleming explained. A Fordham alumnus, Fleming is returning to his alma mater to speak about his book on October 16th as part of its College at 60 lecture series.

What did you study at Fordham?

I studied English. I never took a course in history. I educated myself on that subject. I wanted to be a novelist more than anything else, and I have written 23 novels. I read 700 books in four years at Fordham. I kept a list.

At 17, you joined the Navy and were in the first integrated company. How did that affect your writing of this book?

This book was partly inspired by that. This was one of the greatest experiences of my life. I slept with a black guy on this side, a black guy on that side, and a black guy in the bunk above me. And we got along great. I never saw one rotten thing said to a black guy or vice versa. One of the diseases in the public mind that caused the Civil War was this morbid fear of blacks that was in the American South.

You say one of your goals in writing this book is to forgive both sides.

Exactly. If we can understand that the South had this terrible fear. The trouble was that the North hated the South even before slavery. I have this great quote in the book. Lincoln says, "If you would win a man to your cause, first convince him that you are his sincere friend." The abolitionists didn't know how to do that; they never even tried.

You speak about the presidents before Lincoln and how they all discussed slavery. Washington, for one, was against it, but was scared.

Washington's slaves owned boats! And some of them owned guns, so they'd go out hunting. I call him, "The Forgotten Emancipator." Washington was really in favor of freeing them. It's hard to grasp this now because we've been a united country for so long, but he knew as a general in the army, that people were splitting in all directions. And he thought, that we have to stay united above all. He saw that if they split up, America would become Europe. Unfortunately, that made it difficult for him to do anything about slavery because he thought it would be straw that we wouldn't be able to deal with.

You bring up the fact that Thomas Jefferson wrote, "all men are created equal," but it took more than eight decades for that concept to become a reality.

He didn't know it at the time, but that was the deathblow to slavery. He was, as I call it, "slavery's unintended friend." Because he couldn't believe in the equality of blacks and was terrified of a race war.

There was an anti-slavery organization in New York.

Like most New Yorkers, they tended to be somewhat more moderate. They were still against slavery, but they were willing to realize they couldn't free them all at once. So New Yorkers were willing to accept a gradual emancipation.

New York newspapers were very influential leading up to the War.

The New York Herald was the biggest newspaper in the country at that time and they were Democrats, so they hated Lincoln and abolitionists. The New York Tribune was run by a wild-eyed guy named Horace Greeley. He wrote a letter to Lincoln saying, "What are we going to do? I haven't been able to sleep for seven days and seven nights." Greeley ran a headline in the paper, "Onto to Richmond." That started the Civil War.

So the Civil War basically started in New York.

That's a very good point. I never thought of it that way.

There was even a rally in Union Square with 50,000 people.

Yeah, it was run by the abolitionists. They were screaming, "We have to march; we have to get them!"

In my high-school U.S. History class, I had to do a paper on the fact that Lincoln did not believe in equality for blacks. You touch upon this in your book.

He said again and again, "I'm not an abolitionist." He didn't go for their rather radical approach. But he learned during the war. One of the great moments in the book is when he wrote the Emancipation Proclamation and gave one of the pens he used to a guy who had written a history about blacks in the Revolution. In the Revolution, Washington recruited blacks into the army. This is where Lincoln got the inspiration to enlist blacks in the Union Army. Two hundred thousand blacks fought in the Union Army and, believe me, this changed Lincoln's opinion on whether they were equal or not.

In your opinion, what was one of the most moving moments in the book?

Lincoln's last speech he gave from the White House window. When I was writing that last chapter, several times, I had to stop and wipe my eyes. It was so heartbreaking. You knew he was going to get killed in about 10 days. Here he was, saying, "We have to give the blacks who are intelligent and have an education and the men who fought in the army, the vote." This was a real big change from the Lincoln who started the War.

You went to the New York Society Library to research this book. What's another favorite historical place of yours in the city?

The Society Library is the oldest private library in New York, founded in 1754, believe it or not. It's on East 79th Street, just off Madison. [I also like] Fraunces Tavern [in the Financial District] where Washington said farewell to his officers at the end of the Revolutionary War. He invited all who were left and they clinked glasses and said, "We were a band of brothers, never forget that."

For more information on Tom's event, visit www.fordham.edu/collegeat60