A Cry in the Stark: "Red Dog Howls" Forces Its Cast to Work Very Hard

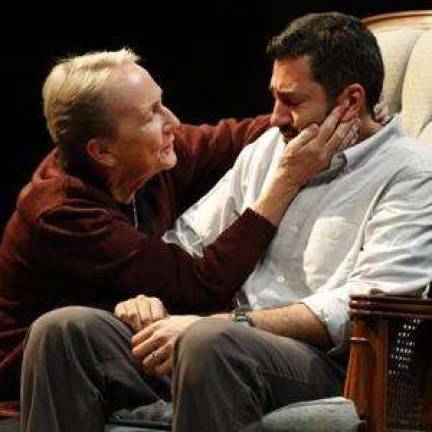

Playwright Alexander Dinelaris apparently spent years working on Red Dog Howls, the new drama currently running at New York Theater Workshop. And his opus, which addresses the savage genocide committed in 1915 by Ottoman Turks on the Armenian population, aims for tragic heights. But the show is mostly sad because it falls short of its dramatic potential. Also sad is that the show, directed by Ken Rus Schmoll (Death Tax, Middletown), underserves the skills of its three outstanding stars, Kathleen Chalfant, Florencia Lozano, and Alfredo Narciso, forcing them to carry this history-lesson-disguised-as-play. Narciso plays Michael Kiriakos, a New York native in the 1980s who is surprised to learn that he is of Armenian heritage following the death of his father. As narrated by Michael, he finds a box with a request from his father to bury it without looking at the items inside. But he notices a return address on some letters, and checks out the woman, Rose (Chalfant), living at the Washington Heights address. Encountering Rose plummets Michael through a rabbit hole of self-discovery and uncomfortable reckoning. Rose, a bluntly perceptive nonagenarian, reveals secret family connections and a whole history pertaining to the Armenian murders. Michael becomes obsessed with unearthing this hidden history, and continues to visit Rose to learn more, in a starker sort of Tuesdays with Morrie set-up, even at the risk of neglecting his pregnant wife, Gabriella (Lozano, making do with what little material Dinelaris has given her). It's admirable that Dinelaris wants to shed light on such an important historical episode, one that is still moving to many of the descendants affected by it and one that, nearly a century later, remains unknown by many as a chapter in the book of world history (nearly 1.5 million people were killed, and the Turkish government to this day tries to dispel the ways events played out). But the playwright approaches his story clumsily ? it is both clinical and melodramatic, when it should be dynamic and engaging. Michael spends too many chunks of the play addressing the audience in platitudes reminiscent of the beginning of Robert Woodruff Anderson's I Never Sang for My Father (which featured a platitude like "Death ends a life. It does not, however, end a relationship"). Luckily, Schmoll has assembled top-notch New York talent, and Narciso, an actor of immense credibility and stage presence, can sell these monologues like Rumpelstiltsken spinning gold. But the cumulative effect of the play is desultory, with Schmoll not doing much to bring energy to the play. Solemn subject matter doesn't equal somnambulism. Howls only becomes a truly dramatically engaging work in its final scenes, and that is also when the play becomes it's most flawed and familiar-feeling. As it wears on, Dinelaris also echoes works like Shirley Gee's Never In My Lifetime and William Styron's Sophie's Choice, forcing both Chalfant and Narciso to stencil in motivation and understanding that the writing itself doesn't always justify. It should be noted that Chalfant, practically a deity of the theatre, prevails even during the most challenging of scenes, as Rose recounts unfathomable horrors and communicates, even wordlessly, an entire lifetime of sacrifice and survival. But one wishes these actors had the words on their side more often. Howls serves up a trio of New York's finest talents ? but all three deserve a better meal than the problematic, though well-intentioned one, on display here. Red Dog Howls New York Theater Workshop, 79 East Fourth Street, East Village; (212) 279-4200, Through Oct. 14.