Bitch-Slapstick

Nichole Holofcener's latest humane insight in Enough Said

Most independent filmmakers demonstrate a desire for attention and recognition more than to express sincere or original feelings. Because so many of them come from the same class of hustlers and achievers and go through conventional production procedures (conveniently known as Sundance), their films look alike, reflecting the same ideas about storytelling and character. Because fake sensitivity and glib "complexity" don't communicate fresh truths, the majority of indies end up elite vanity productions that belong to a category of middle-class narcissism.

And then there's Nicole Holofcener who makes that narcissism her subject. Holofcener's new film, daringly titled Enough Said, cites the limitations of middle-class self-absorption and lightly but movingly traces it to the personality of Eva (Julia Louis-Dreyfus), a Los Angeles divorcee and mother who works as an independent massage therapist (perfect indie metaphor). Introduced carrying her portable massage table to assorted clients, tiny Eva's baggage is bigger than she is.

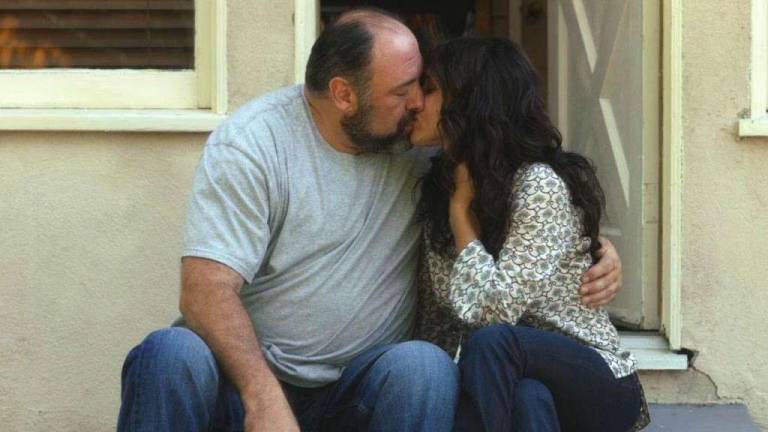

Holofcener views Eva's need for companionship--her single-woman frustrations and confusions--through a balanced dramatization of basic emotional involvements that lead her to Albert (James Gandolfini), her burly physical opposite but also a divorced parent. Instead of rom-com fluff, Holofcener keeps the courtship simple. Their hook-up culminates in a stunning post-coital admission: "I'm tired of being funny."

In Enough Said, Holofcener draws the line at indie self-amusement--cleverness for its own sake--through a clean, airy, open-hearted style that mixes awkwardness with humorous recognition of the quirks and weaknesses people share. (A disastrous dinner party scene trades chagrined faces.) This unusual gift has been honed through four previous films, struggling against indie narcissism, getting riskier all the time. Honestly womanly, Holofcener's never shied away from showing her female protagonists' bitchiness. Her roles for steady collaborator Catherine Keener have been brusque, sensitive and truthful--a kind of muse, this time presented as Marianne, another divorced mother but also a glamorous, tasteful, self-assured poetess, also seeking friendship.

Eva's confidences with Marianne complicate her romance with Albert in devastating ways. Holofcener reveals Eva's insecurities without the formulaic cuteness of Nora Ephron movies (which always made the revered Ephron a Hollywood hack). Eva's self-defeating envy of Marianne's fabulousness is a genuine class and gender insight. Eva is the ultimate Catherine Keener role which may be why Holofcener's assigned it elsewhere--to Louis-Dreyfus who's up for the challenge. After so many years as funny, coarse Elaine Benes on TV's Seinfeld, it's surprising to see her look stricken; her face open to hurt, not hard cuteness. Through Eva's shame (she laughs off a rough, sexist insult) and Albert's masculine vulnerability, Holofcener attains Mike Leigh's poignancy on her own terms. It's a sit-com breakdown and an indie-movie breakthrough.