EAST VILLAGE TRANSPLANT

A New Hampshire ex-pat charts the cultural shifts born and bred in Downtown Manhattan

By Danny Gold

Anthony Pappalardo is not a fan of the term cultural historian, especially when applied to him. He is even less enthusiastic about being referred to as an expert on youth subculture. In fact, Pappalardo bristles at those descriptions. "I'm 36 years old. If I referred to myself as that, I'd be a creep," he said.

It'd be hard to argue, however, that Pappalardo does not possess an encyclopedic knowledge of many of the subgroups popular in the late 1980s and '90s, whether skateboarding, punk, hardcore or a host of others. In Pappalardo's new book Live...Suburbia! (powerHouse Books), which he co-authored with fellow savant Max G. Morton, he chronicles the suburban upbringing and rites of passage that resulted from an embrace of some of these movements, especially with regard to music and skateboarding.

The East Village scene played a pivotal role in the formation of hardcore punk and street skating, among other subcultures, so it's no surprise that the book traces Pappalardo's journey from the suburbs to Downtown Manhattan. "This could not happen in Los Angeles or any other city, because in New York, the most recognizable people take the subway, go to dive bars, buy records and get coffee like the rest of us instead of eating power lunches at crappy L.A. bistros in shades-no one cares here," he said.

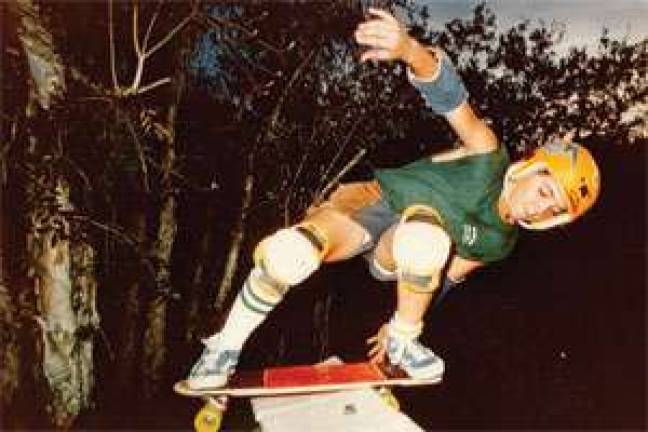

Pappalardo spent most of his formative years in Salem, N.H., a typical suburban New England town, before moving to Boston to attend the Massachusetts College of Art and Design. A music junkie, he later played in seminal hardcore bands like In My Eyes and Ten Yard Fight, and found himself living in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, in 2002. He describes his adolescence in the book by stating, "I rode a skateboard, a BMX, kept weapons in my locker, cursed a lot, liked heavy metal, lit things on fire, jumped off of stuff and, if anyone I knew would have surfed, I would have been a walking Black Flag lyric."

A conversation, let alone an interview, with Pappalardo can be a bit of a trying process if you are not steeped in hardcore music or skateboarding culture-or any late-20th century subculture, for that matter. Answers to questions veer off into many different directions, with frequent references to obscure bands, skateboarders, defunct clothing lines and long-since-closed bars and music venues. It's not that Pappalardo is pretentious about these things; they have played such a large role in his life that it seems almost impossible for him to imagine someone in their twenties or thirties without a similar knowledge base.

His voice and mannerisms bear a slight similarity to the director Spike Jonze, which is actually quite fitting considering the contribution Jonze made to the collective culture of the 1990s.

"Anthony is not some historian in glasses and a sweater. He's a writer with a great eye who loves music and grew up in the skate and punk subcultures," said longtime friend and fellow writer Ray Lemoine. "It's clichéd, but D.I.Y. was always how he did things. He taught all our friends that an idea could not only become real but also successful. That's his gift: quality creations and giving his friends belief in creating."

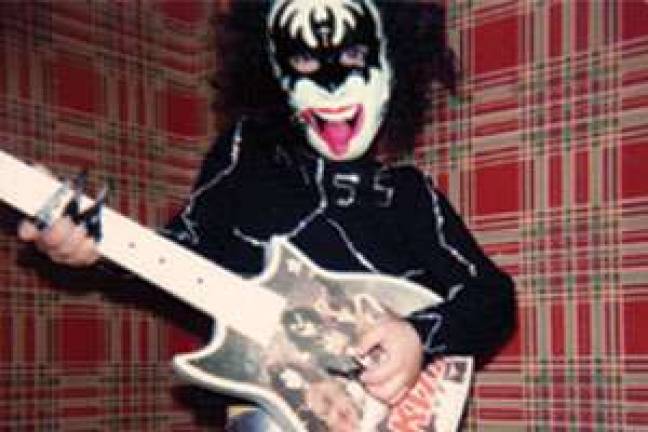

The book itself is comprised of short vignettes from Pappalardo and Morton's preadolescence through their college years and contains some of the usual rites of passage faced by any suburban teen: falling in love with a genre of music, chasing after girls and highs, skateboarding, building bike jumps and getting into fights. But it also includes pointed critiques and explanations of what liking a certain band or clothing item meant, and how important it was for youth during this time to express themselves through these signals.

"The heart of the book is adding context to what you see around you," said Pappalardo, referring to the way these once-fringe subcultures contributed to the popular culture by which we are now surrounded.

The book also contains of hundreds of photos from the same era. These photos capture the amazing(ly bad) fashion of the time, concerts in small VFW halls, the party scene, the metal kids, the stoners, the goths, the punks, skateboarding and many of the bands. The '80s and '90s are portrayed so vividly and accurately that John Hughes would be embarrassed to compare his own work to it.

"We started with an archive, then we just started reaching out to people. We told them, 'Your moments as a kid are embarrassing, but they're iconic. This isn't a Vice Do or Don't, we're not going to clown on you,'" Pappalardo said.

What followed was a long cold-calling process, with Morton and Pappalardo simply dialing up the people whose photos they thought would work. The photographer Angela Boatwright was an early supporter, and her seal of approval led to others acquiescing. A corrections officer named Aaron Malejko provided Pappalardo with a treasure trove of house party photos. In a story reminiscent of an '80s movie plot, Malejko's parents moved out of town before his senior year of high school and he decided to stay behind and rent his own place.

The stories shared are a lot more personal. While Morton's read a little like spoken word poetry, Pappalardo's are oddly touching. And while they are taken from his own history, most kids who grew up in suburbia with vaguely similar interests can probably relate to any number of the passages: drinking stolen beer in the woods, hopelessly lusting after punk rock chicks too cool for him, facing down bullies, discovering music, attending shows.

Viewed as a whole, the stories encapsulate a moment in history. Much as Harmony Korine and Larry Clark's Kids aimed to do for urban teenagers growing up in Downtown Manhattan, Pappalardo's stories could almost be used as a history textbook, albeit a very graphic one.

"It's that suburban thing; everyone can relate to it," he said. The book serves as an ode, an homage of sorts, to this upbringing. A lot of Pappalardo's inner musings capture the typical longing in the suburbs to escape to somewhere "cool" and the later-in-life realization that growing up in the suburbs might have been pretty rad in itself. "These stories were chosen specifically because it was like, where are you going and, once you get there, what are you doing with those opportunities?" he said.

A big part of that is the epic quest for "cool" and the sense of trying to belong, whether by the bands you listen to or the clothes you wear or the skateboard you ride. "It's about longing for a bridge from where you are," Pappalardo said. "I grew up a dreamer."

This wasn't 2011. Skateboarding and alternative types of music were not popular, nor were they something many people in his hometown supported. The blend of cultures that exists in today's post-mash-up world was nonexistent. "I gravitated toward the people who were into those things, those who knew there was more out there and wanted a community of like-minded people," he added.

These communities of likeminded people were essentially tribes, Pappalardo explained. You showed your allegiance to a certain tribe by which brand of sneaker you wore or which record or cassette you showed off. Back then, it was a big deal if you chose to wear Airwalk or Fred Perry. "What you're trying to establish is, 'I'm a part of this tribe.' The tribal identity was so important prior to the commoditization of subculture. You were saying, 'I'm this person,'" said Pappalardo.

All of these tribes apparently had one goal, and that was to end up in the East Village, where they would be heavily represented and everything they searched high and low for would be readily available. The street skating scene was taking off with brands like Zoo York. Kim's video store led the way for a score of other used record stores. CBGB was fostering hardcore music and the Alleged Gallery was bringing skateboard art to the public on a previously unheard of level-not to mention the rotating cast of dive bars and clubs that had their 15 minutes. It was the focal point.

Pappalardo started taking the bus down to New York City in college. "We never went anywhere but the East Village. There were a million record stores, there was 99X, which was the only place you could buy Ben Sherman and Fred Perry stuff," he said, referencing two iconic British brands that were popular with a segment of the skateboarding, hardcore-listening population. "It was all folklore to me."

Pappalardo finally moved to New York City in 2002, but could only afford to live in an illegal apartment in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. He worked for street teams putting up stickers and wrote for skateboarding magazines.

As for the East Village, it was the holy grail. "Anything you fantasized about was there. You had the best clothing stores, the best record stores, the best music venues where the best bands played," said Pappalardo, mentioning the likes of CBGB and Supreme, icons of punk and skateboarding culture.

But this is where he takes a slight turn and starts to describe why he finds the suburbs more compelling: "Whatever happens in New York City, you need kids in suburbia to be into it."

And for Pappalardo as well as for many other teenagers for generations, the East Village has been a place where the people in these subcultures gather to find like-minded individuals. "We never appreciated what we had-we were always looking forward to getting to the East Village," he said.

Pappalardo also recently finished writing his first story. "It's called 'Granite Pace'; it's a really simple, John Hughesy story about a skate punk, hardcore kid and his bond with a popular chick with a dark secret or something like that," he said.

He's also returned to music and has an album coming out on DAIS records (who also produce the bands Cold Cave, Psychic TV and Iceage) with artwork by Robert Pollard of Guided By Voices. His solo project is titled Italian Horn and is a bit of a diversion from his previous work in the hardcore scene.

Pappalardo is also already working on a new book and is promoting Live?Suburbia! all over the United States.

As for the current incarnation of the East Village, he's uncharacteristically reticent about how he feels about it. He doesn't seem that upset about gentrification, and comments that he doesn't mind not getting robbed there anymore. Whether the neighborhood still has the same pull for misfits across the world, he's not sure.

"I'm so far removed from youth culture that I don't really know whether there are still 14-year-old kids in the middle of nowhere longing to come here, but the identity of the East Village is still very important," he said. "And I know that people my age are making a living by commodifying it."

Still, it's hard not too imagine he's a little dissatisfied with everything. In the book's last vignette, after witnessing a baby in a Motörhead T-shirt, he writes:

"As I continued to scan walls, magazines and humans, I noticed that every novelty from my childhood was now a movie and a sequel. All bands, dead or alive, were back together and playing festivals where they charged you for water. I was in New York City, but I suspected this phenomenon was spreading through America and maybe all of Earth?All the humans I wanted to meet as a suburban teenage boy in the late 1980s had become franchises in my hometown mall. The convenience was great but still confusing."

------

Pappalardo's Playlist for his Generation

Black Sabbath, "Black Sabbath" Hard rock, glam rock, metal...whatever I had been exposed to prior to hearing Black Sabbath seemed tame, lame and a waste of my fucking time. "Iron Man" and "Paranoid" were already in my brain somehow through radio shows and mixtapes, but "Black Sabbath" was the song that left the biggest impression. It barely sounds like music-it's not conventional blues rock, it's just three notes and a disturbed man screaming and babbling over it.

Slayer, "Black Magic" Sabbath crushed, galloped and crunched. When I found out there was a breed of heavy metal based on speed, I was hooked-and also terrified. There was always this stereotype of metal being satanic or evil; Slayer lived up to every stereotype from their sheer speed and lack of melody to the pentagrams and other imagery made to piss people off. Just the sight of their logo on your denim jacket sent a nihilistic message to the other people around you the mall, school or woods.

Minor Threat, "In My Eyes" Something happened to me in my early teens...a switch was turned and I woke up thinking heavy metal was a boring, cartoonish fantasy. I didn't stop listening to it, but its impact was gone. Minor Threat played a key role in making metal seem tame. Punk rock led me to its American cousin, hardcore, and I was hooked. Fast, direct music played by kids in jeans and T-shirts-it was deceptively simple. Minor Threat stand as one of the most popular hardcore bands of all time, but they cannot be replicated.

Mission of Burma, "That's When I Reach for my Revolver" WFNX, Boston's alternative radio station, would play MoB in regular rotation, despite the fact that they had been broken up since the early 1990s. They'd be sandwiched between The Cure's new single and a Morrissey song-I thought they were as big as those artists. I didn't realize they were infinitely more influential than "big." We'd buy any record related to MoB, from Pere Ubu and Wire to countless indie rock bands of the early 1990s that name-checked them. I'd listen to Burma and imagine what it would be like to see them in the same way I'd wonder what it would be like if Buckner had fielded the ball and the Red Sox had won in 1986.

Sebadoh, "Scars Four Eyes" Seemingly overnight, most of my friends went from aggro skate punks living at home to confused kids in dorm rooms discovering these new things called emotions. I'm pretty sure every dorm room in Massachusetts came with a copy of Sebadoh's record. Luckily for us, Lou Barlow was our cool upperclassman, figuratively speaking, who had been through punk and hardcore and was now digging through the crates for Nick Drake records. Top Photo: Author Anthony Pappalardo outside an East Village skatepark on 12th Street that's part of a local school. PHOTO by Jonathan Hökklo | hokklo.com