Essay Collection Casts Off the Burden of Shame

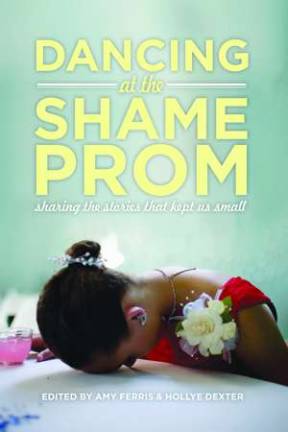

By Beth Bellow As an intrepid 10-year-old bug huntress in small-town Pennsylvania, Teresa Stack's biggest achievement was the capture of one of the most elusive, and venomous, bugs-the cicada killer. The day she victoriously trapped one of these insects for her burgeoning collection, she ran home to show her father, who chuckled and said, with pride, "I'll be damned. You got yourself a cicada killer." The thrill Teresa felt as a result of the catch and her father's approval would be short-lived. One night, thinking that she heard the cicada killer flap its wings and come alive even though it was securely mounted on a board on her bedroom wall, she smashed the bug, and the rest of the collection she had assembled, into pieces. In that moment, the tenuous bond she shared with her alcoholic father, their passion for insects and nature, had been severed. "The Cicada Killer" serves as symbol and title of an essay in which Stack narrates her fraught and complex relationship with her alcoholic father. As part of the anthology Dancing at the Shame Prom: Sharing the Stories that Kept Us Small (Seal Press; $16; edited by Amy Ferris and Hollye Dexter), Stack, now forty-something and president of The Nation, whose offices are near Union Square, tells the readers of the unpredictability and fright of living with an addict. "It was terrifying, absolutely terrifying to put my story on paper. You think you will actually be shamed even more by sharing it with others, but it was cathartic. Not only did I not experience more shame, I actually got empathy and acceptance," Stack said. This was the goal of the editors, Ferris and Dexter, in creating the anthology, which includes a multitude of stories by women from all walks of life. According to the women who contributed to Dancing at the Shame Prom, shame comes in all different shapes and sizes. "The book has something for everyone. There are stories of small shames and big shames, but all end on a redemptive note," Stack said. One contributor, Upper East Sider Marcia Yerman, discusses the shame of feeling different from other young kids on the playground in her essay "The Jump Rope Line." She suffered from an anxiety disorder and sensory integration disorder, which made her hypersensitive to stimuli. "If I was on the school bus with a bunch of screaming, rowdy kids, it got to be really overwhelming," Yerman said. Yerman eventually found solace in art, and has become a successful writer and curator. As an adult she has kept her anxiety, for the most part, at bay with the help of therapy and meditation. Additionally, she has developed an appreciation for what makes her different from other people. "From a very young age I had been pegged as 'overly sensitive,' but this has also enabled me to be more sensitive towards other people's feelings and to be empathic towards them," she said. Contributor Robyn Hatcher also explores the feelings of isolation she experienced as a young child in her essay, "Stinkin' Shame." Hatcher recalls that her family always accompanied evening newscasts with a chorus of mournful remarks. It was the 1970s, and not only were there no African-American newscasters, but all the bad news seemed to focus on African-Americans breaking the law. This was a "stinkin' shame"-as far as Hatcher's grandmother, mother and other relatives were concerned. "When my family was so anti these African-American people who did these bad things, I had to find a way to define myself. I felt it was my mission to prove this [thesis] wrong," she said. To achieve this "mission" and to cope with a deeply entrenched shyness that followed her into her teenage years, Hatcher made it her goal to be "super special black girl." She excelled in school and thrived in the drama club. Today Hatcher, who dwells near Union Square, is a successful business owner who feels at ease with her racial identity. She marvels at the leaps and bounds we have made as a nation, from the election of Barack Obama as president to the feeling of acceptance her biracial son, now a senior at Yale, has experienced throughout his childhood. She said, "My son can hang out with his predominantly white fraternity, but also take an African-American studies course." What has also helped Hatcher is sharing her feelings of shame with others. She said, "The thing about shame is, the more you talk about it, the more it dissipates."