Iraqi Refugees Find Art Outlet on Upper West Side

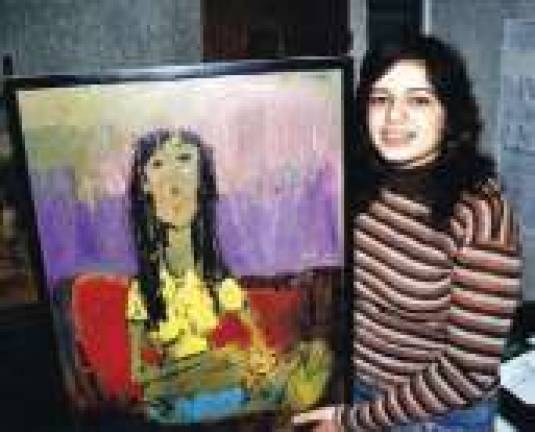

New Yorkers have a chance to help Iraqi refugees half a world away while simultaneously beautifying their walls with original art. The nonprofit organization Common Humanity, founded by Upper West Side resident Mel Lehman, will show 22 new paintings by Iraqi artists currently exiled in Damascus, Syria. Lehman found a home for the exhibit at the Second Presbyterian Church on West 96th Street, where it will be on display from April 13 through May 12. The paintings, ranging in style and medium but all exhibiting lush, bold colors and striking depictions of people, landscapes and abstract images, are the works of artists for whom painting is literally a lifeline. The money raised by silent auction during the exhibit will go toward Common Humanity's continual trips back to Damascus to purchase more paintings. "The basic purpose is to try to build some connection and some understanding between the Middle East and the West in this terrible conflict in which we find ourselves," Lehman said. He started the organization three years ago, quitting his job and supporting himself as tour guide on the ubiquitous red buses that crisscross the city. Lehman had traveled frequently to Baghdad for work and seen firsthand the conditions of Iraqis living under sanctions during Saddam Hussein's rule there before the U.S. invasion. Later, when he became aware of the large Iraqi refugee population in Syria, he founded an organization that would help bridge the cultural gap between the U.S. and the Middle East as well as provide tangible help for the refugees. "I think that the congregation's response has been really positive, because it feels like we're helpless to do anything about what has been done, but we can do something," said Leslie Merlin, the pastor at Second Presbyterian. There are currently over a million Iraqi refugees living in Syria, according to the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees offices there, and the government allows them to find homes, send their children to public school and access basic state-funded health care-but it doesn't allow them to hold jobs. "What they can't do is pick up their careers where they were. They're living at the very margins but they are subsisting," Lehman said of the refugees in Syria. All of the artists Lehman buys from have been professionally trained, and many were successfully supporting themselves in Baghdad before circumstances forced them out. One pair of artists who have sold paintings through Common Humanity, a couple, became targets of a local militia in 2003 after one of them began drawing pictures of the American soldiers entering their neighborhood. They fled for Syria after receiving death threats. Another artist, Ahmed Al-Karkhi, left Iraq for Syria in 2006, continuing to paint and sell his work in Damascus. Eventually, in 2010, he was able to settle in Washington, D.C. Now he works days as a janitor but still paints, and his art has been shown at D.C. galleries as well as in countries around the world. "It's a huge silent humanitarian crisis that's going on [in Iraq]," said Cecilia Blewer, a congregation member at Second Presbyterian who works closely with Common Humanity and has traveled to Damascus with Lehman. The paintings sell for a range of prices, but $500 is an average going rate-a bargain compared to other original work sold in galleries in Manhattan, but enough to sustain a family in Damascus for several months. For Blewer, facilitating the sale of the paintings isn't just a beneficent way to share good artwork, it's a moral imperative. "Basically, we flattened Baghdad and we caused this exodus, including this diaspora of their intelligentsia and their artistic people, who are probably fairly suspect anyway in the new regime," Blewer said. Lehman and Blewer are planning to go back to Damascus in June and hope to expand the exhibits by taking them on the road. "We basically feel that in this time of really terrible conflict between the East and the West, we need to establish a bridge," Lehman said. "We seem so separate and so different from each other; we try to understand these different cultures, what makes us common as human beings."