Obliviots, or Deeper Into Solipsism

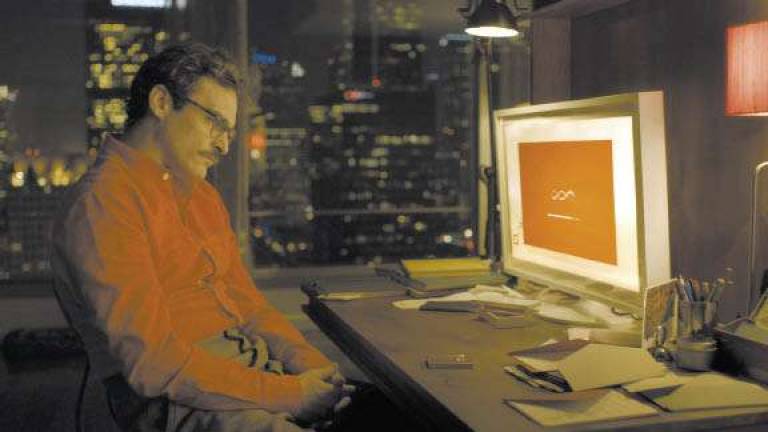

Casting Joaquin Pheonix as electronic greeting card writer Theodore Twombly is immediate overstatement. After Paul Thomas Anderson's The Master, Pheonix is poster boy for creepiness even before he can develop the quixotic personality of a solitary divorce employed in drone-like work ((by BeautifulHandwrittenLetters.com !) to manufacture hollow sentiments for paying customers. (Theodore's emotional prostitution embodies the thanklessness of grunt-jobs; former skater-boy Jonze conveys the hipster generation's pampered alienation from the workaday world.) This postmodern disaffection (carried-over from The Master's facile agnosticism) makes Theodore's eventual "falling in love" with an non-human--his computer's operating system--all too expected. Given the film's hushed tone, you knew something weird is coming: his OS has the feminine name Samantha (voiced by Scarlett Johansen).

But there are no life-like surprises in either Theodore's high-waisted nerd apparel or Samantha/Johanssen's sultry, teasing voice. The film's oddly mannered visual style represents a slightly futuristic Los Angeles/Hollywood of Apple-affluent sleekness--an air of undeniable consumerist elitism. With Jonze directing his first feature-length solo script, the movie is all concept and, frankly, it's a terrible idea--not screwball farce but Eccentricity for its own sake. Jonze may get freaky in his contributions to Bad Grandpa, even playing an oddball clerk in The Wolf of Wall Street, but Her is a concession to the commercialism that even hipsters don't realize they enjoy.

Eccentricity Gets Tested: I'm Here premiered simultaneously with Zack Snyder's visionary The Legend of the Guardians: The Owls of Ga'Hoole--a film whose projection of human feelings onto other species ranks as a companion piece to Where the Wild Things Are. But neither Eccentric Masterwork (Owls and I'm Here) was a commercial blockbuster. So this time Jonze doesn't risk asking audiences to extend their imagination toward anthropomorphism. Her pretends to confound human emotion and amatory attraction. Not an update of the Pygmalion and Galatea myth, Her merely reworks the premise of I'm Here. Theodore's relationship to Samantha abstracts Love into something non-profound; it becomes a mystery that is illogical, anti-romantic--a safe confirmation of nihilism, commercialized negativity.

Because Jonze's instincts are very much au courant--more hipster-cool than avant-garde--lazy viewers are willing to accept the film's trendy conceit as a challenge to virtues they already disavow. Her is a love story designed for those too scared to believe that love is possible and so are not offended by its mockery--an adolescent, skater boy bluff.

Jonze doesn't mock the idea of love so much as its human improbability. (This is where Her differs from classic Screwball which, like Shakespeare's comedies, always perpetuated the need for human connection.) Theodore's co-workers (Amy Adams as his heartbroken colleague, Chris Pratt as his fatuous boss) demonstrate the sadness and shallowness of romantic alliance and his ex-wife (Rooney Mara) confirms its impossibility, hidden in distrust and disloyalty. Humans are seen as uncommunicative and unrealiable--that's why Theodore goes over to the other side.

In Her, Jonze romanticizes the solipsism of obliviots, middle-class digital device idiots who lack the impulse to resent how technology damages their senses, limits their humanity. His scenes of Theodore alone on a beach or walking through snow drifts are shot ironically but lack a Chaplin or Keaton sense of humor. Jonze's eccentricity should have saved him from indulgent solipsism, the snarky normalizing of digital era detachment, isolation and alienation. Her's biggest shock is that Jonze loses his sense of funny; it's unromantic yet is unacceptably sentimental.