The Long Picture Show

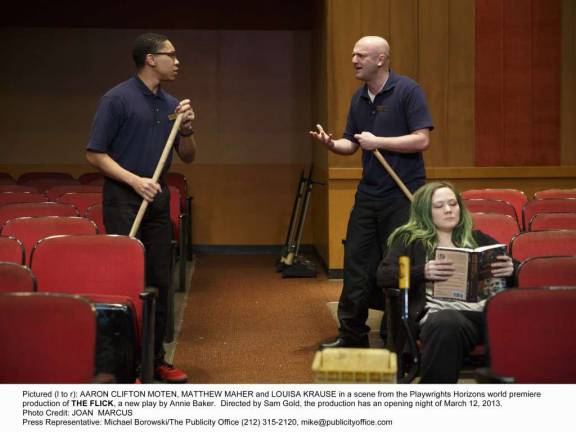

'The Flick' could benefit from some editing In The Aliens, the last original play of Annie Baker's to run in New York, the playwright employed what I refer to as the "gotcha moment." At one point, a character breaks from the measured, elliptical style with which he, like all the others, have been speaking, slowly clueing the audience in to who they are and why they are the way they are, with a blunt confessional statement that turns everything on its head. It is not a stunt, because all that has preceded it and all that follows has been earned. Used once, it packs a visceral wallop. But used several additional times in The Flick, Baker's latest play which just opened at Playwrights Horizons, this device has now become one of the writer's hallmark effects, and its overuse, among other choices employed in this play ? a well-intentioned misfire that is equal parts promising and frustrating ? suggest that Flick has not yet arrived at the final cut stage. With just three original plays under her belt ? Body Awareness, Circle Mirror Transformation, and Aliens ? Baker catapulted from promising voice to important talent in an instant. Her singular gifts lie in her observations, usually set somewhere in the small-town New England where she grew up, of socially stunted and broken people. In addition to that gotcha moment, she also employs devices like the awkward pause, hesitations, and repetitions to reflect the tentative and quirky links formed among strangers and the inherent but subtle power structures built within such relationships. Her plays, staged by the ubiquitous and similarly intuitive director Sam Gold (they also teamed up on last summer's adaptation of Uncle Vanya at Soho Rep), have hit the sensitive bull's-eye on the intersection between the humor and heartbreak of human folly. Baker introduces characters similar to the ones we've met before in her world in Flick, whose title comes from a run-down movie theater in Worcester County, Massachusetts. There's Sam (downtown stalwart Matthew Maher), the 35-year-old nebbish who resents that 24-year-old Rose (Louisa Krause) gets the privilege of running the projection booth at the same time he quietly pines for her, and Avery (Aaron Clifton Moten), the 20-year-old cineaste who has taken up work at the Flick while on a sabbatical from Clark University, where his father is a professor. He's a purist who has been drawn to the local theater because it is one of the remaining few houses to use a 35-millimeter projector, as he hates the trend of digital moviemaking. (The marvelous set designer David Zinn has fashioned the theater in all its dilapidated glory.) Baker has buried plenty of golden nuggets here among the threesome's quotidian chores as theatrical custodians and concessionaires. As Sam and Avery bicker over which films from the last decade matter (the former declares Avatar a masterpiece; a horrified Avery avers that there has been no such thing such Pulp Fiction), their subtle verbal and non-verbal tics shade in volumes about what draws each of these outcasts to the Flick. And as the grungy Rose overshares details of her own life to Avery, we learn she isn't even aware of him after a while; she just craves an outlet. Flick is a departure from Baker's earlier catalog in ways big and small. It's certainly epic in length, if not in ambition, as we're alerted from the get-go by a musical interlude that runs several minutes in length. And Baker's rhythmic sensibilities are bar none. But Baker seems to think she has accomplished more than meets the audience's eye. The fundamental flaw in Flick ? and despite the play's attendant nuance and riches, this is, sadly, both a flawed play and a flawed production in its current form ? is that none of the relationships between the three main characters is strong enough to support the themes of loyalty, betrayal and connection for which Baker strives for by play's end. (Alex Hanna also appears as a couple of minor characters). Several of the play's most noteworthy, illuminative moments ? a one-sided telephone conversation, an impromptu hip-hop dance, several revelatory monologues ? stand out as solo sequences rather than reflect any real sense of bonding. In other ways, Baker seems to distrust her own narrative abilities, and Flick, which runs three hours and fifteen minutes (including just one hurried intermission), suffers from this lack of economy. A first act sequence in which Sam reacts to Rose's surprising invitation of Avery to a film screening that's a de facto date is priceless, benefiting from a perfect tableau on Gold's part, and providing all the shorthand an audience needs about how each character feels; a subsequent scene in which Sam tries to explain his feelings to an unreceptive Rose feels, labored, amateurish and melodramatic. It's unnecessary and slows down this overlong show. So, too, do late scenes involving the Flick's transition to a modern, digital cineplex. Simply seeing characters in an ugly new corporate uniform (the busy Zinn's costume design is appropriately unflattering for all characters involved) implicitly informs the audience what Baker's characters go on to belabor. This is unfair. You don't have to cater to the lowest common theatergoing denominator, but if you plan to tax audience patience, the rewards should pay off in dividends. Flick is also physically clumsy. Gold obscures too much interaction in the upstage projection booth. And while Baker has peppered the play with myriad film-title-dropping, it's hard to be sure whether they are random references thrown in or if they are carefully chosen films meant to elucidate her characters. What, for example, does Pulp Fiction specifically mean to Avery? We never learn. Why, too, does he whistle "Le Tourbillon" from Jules and Jim? It takes more than scribing two girls and a guy to earn comparison to that masterwork. In Amy Herzog's The Great God Pan and Samuel D. Hunter's The Whale, two earlier Playwrights Horizons shows that stand out as highlights of the current theatrical season, entwined literary references to mythology and Moby Dick, respectively, in a far more essential manner. The cast, however, refuses to be weighted down by Flick's narrative ambiguities. With perfectly understated physicality, Maher, an alum of this summer's Vanya, telegraphs his frustration as one of those nice guys who seem invisible to most, and his humor emanates naturally from Sam's disappointments. Krause is a perfect fit for Baker's material, nailing every cadence of Rose's lost, mercenary soul. And with a perfectly calibrated clipped delivery, Moten makes an incendiary New York stage debut. His Avery, still at a loss as to how to properly arm himself against a world of hurt and disregard, is heartbreaking. And yet for all the careful emotional spelunking done by this superlative cast, Flick leaves their characters lost at sea, intuiting a tighter bond among these three merely coexisting souls than truly exists. For all the film titles thrown about, Baker has omitted the one that unfortunately, feels the most apt: Being There. The Flick Playwrights Horizons, 416 W. 42nd St. [www.playwrightshorizons.org](http://www.playwrightshorizons.org) Thru April 7.