A Collective Portrait

In 1939, W.H. Auden, the English-born American author, composed a poem. Its title, “September 1, 1939,” commemorates the day that Germany invaded Poland, initiating World War II. Auden wrote about sitting in a bar — a dive, in his words — on East 52nd Street as he ruminated poetically on history, society, individuality, love, anger, despair, responsibility, affirmation and hope. In 2017, for his first installation drawn exclusively from the holdings of the Whitney’s collection of American art, curator and director of the collection, David Breslin (along with Jennie Goldstein and Margaret Kross) has taken that poem as a lens through which to look at art and artists and how they see certain issues. By doing so, he’s created a deep, layered, moving portrait of not just America’s art, but its heart.

Focusing on works made between 1900 and 1960, the exhibition fills the entire seventh floor with works that highlight both the museum’s extraordinary collection and a nation filled with passionate individualism and an experience that encompasses both commonality and diversity. Each of five sections is formed around an idea expressed in Auden’s poem. They include “No One Exists Alone,” a look at love, friendship, family and shared responsibility; “The Furniture of Home,” which explores where we dwell and the objects that make up our everyday lives; “The Strength of Collective Man,” a visual recording of American society’s struggles and triumphs; “In a Euphoric Dream,” in which George Washington’s description of the nation as a “great experiment” yields surprising outcomes; and, finally, “Of Eros and Dust,” which looks at the spiritual foundations of several movements and works. Through photographs and prints, paintings and sculptures, in realism and abstraction, we find reflections of history and life, evolution and strife, and, if we look carefully, ourselves.

We in New York don’t need much to be reminded of the polyglot nature of America’s voice. It’s the hum of the city, surrounding us every day. It’s here, in the show, as well. Several of the highlighted artists like Arshile Gorky, Ilse Bing, Ben Shahn and Abraham Walkowitz were, like Auden, immigrants who came to this country for its promises or protection.

For others, the transcendence of their art is multiplied by difficult paths. California-born Ruth Asawa and her family were taken to a Japanese internment camp. Isamu Noguchi, whose work is also included, challenged the legality and humanity of such camps, and later became their only voluntary internee. Both Elizabeth Catlett and Charles Henry Alston were the grandchildren of slaves. Catlett is represented by a series of linoleum cut prints. They mostly focus on courageous women’s lives, from anonymous field and domestic workers to Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman. The audio (for kids) points out that Catlett preferred to produce inexpensive prints so that the people whose stories she depicted would be able to own them.

Among the earliest works on display are Marsden Hartley’s 1914-15 “Painting, Number 5,” a somber reaction to the beginning of World War I, which, along with William Glackens’ 1912, “Parade, Washington Square,” echoes conflicting sentiments that permeate Auden’s poem. From there, the path is open. “Eros and Dust” deals with the spiritual in art. Georgia O’Keeffe and her less famous contemporary, Agnes Pelton, present lyrical abstractions that blend nature and imagination. Nearby, Morris Louis’s enormous, soaring color field painting “Tet” radiates soothing ebullience in emerald green and waves of blue. Ruth Asawa’s abstract, biomorphic, woven sculpture recalls raindrops or nests. It weightlessly occupies space and fills a window framing the Hudson in a particularly lovely moment in the exhibition.

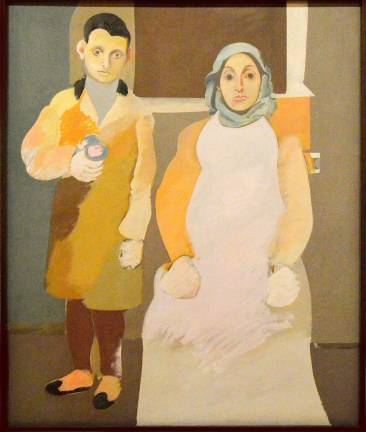

Throughout the galleries, iconic works hang alongside lesser-known pieces. Hopper’s haunting emptiness and Thomas Hart Benton’s crowded “Poker Night” are familiar, as are Charles Demuth’s and Charles Sheeler’s monumentalized factories. Henry Billings’ “Machine Men” and Victoria Hutson Huntley’s “Kopper’s Coke,” both lithographs dealing with similar subjects, were new to me. Sometimes, two great pieces are altered and amplified when seen together. The juxtapositioning of Arshile Gorky’s haunting self-portrait with his mother and Fairfield Porter’s “Portrait of Ted Carey and Andy Warhol” is a deft curatorial touch.

Some of the most beautiful and touching images in the exhibition are in the section titled “No One Exists Alone.” Along with the Gorky and Porter images, there are John Steuart Curry’s paintings that evoke the serious yet joyful rural communities of his youth. Paul Cadmus and PaJaMa (the collective name used by Cadmus, Jared French, and Margaret French) are included with works that, the wall text states, “give visibility to queer relationships that continue, in our time, to demonstrate the commonality of love and to enrich our understanding of what family and community mean.” A stunning group portrait in rich tones of sienna and cobalt, Charles Henry Alston’s “The Family” pulls you from across the room in a room filled with great paintings. Its monumentality, quietude and grace imbue the subjects with as much dignity as was ever painted into a royal portrait by Velázquez or Rubens.

The Whitney’s 2015 inaugural exhibition in its Gansevoort Street building was titled “America is Hard to See,” excerpted from a Robert Frost poem. Pairing poetry and art has enhanced both for millennia. It does so here as well. The exhibition provokes thoughts, delights with favorite works and new discoveries, and creates a rich picture of not just where we are, but where we’ve come from and who we are. Read the poem before visiting, and your experience will be richer. Better yet, print it and bring it, and look at the works of art with its words echoing. From Gordon Parks to Jasper Johns and Alice Neel, we see America through kind eyes. The stanza of Auden’s poem that contains the phrase “no one exists alone” concludes with what has become one of his most quoted lines. Auden warns “we must love one another or die” but ends by challenging darkness and despair with an artist’s, or simply a human being’s “affirming flame.”