A Design Visionary

BY VAL CASTRONOVO

The Brutalist architecture of The Met Breuer is the perfect foil for the whimsical designs of Ettore Sottsass (1917-2007), best known for his work for tech giant Olivetti and the gonzo Postmodern design collective, Memphis, which made a splash in the 1980s.

Pop colors meet concrete in an ambitious show that seeks to put the obscure architect and designer’s 60-year career in context by showcasing items from The Met’s collection that influenced Sottsass — and which were, in turn, influenced by him.

“This is not a retrospective,” Christian Larsen, the curator who put the exhibit together in only nine months, said. “That has the effect of yet again presenting Sottsass as a sui generis, lone genius who doesn’t relate to anything else and can be dismissed as a blip in history. By anchoring him in a historical tradition ... all of a sudden you can make the connections and can understand his importance.”

It’s a tight show that moves roughly chronologically before breaking down into mediums. There’s furniture, industrial design products, ceramics, glass, jewelry, textiles and architectural drawings, displayed alongside ancient and modern touchstones — mandalas, tiny stupas, kachina dolls, Bauhaus textile designs and more.

A small ancient Egyptian box with provisions for the afterlife, including slaves, plays off two of Sottass’ visionary Superboxes (1969, ca. 1970), totemic all-in-one cabinets designed to hold “what you need for modern life,” Larsen said of the conceptual pieces, covered in plastic laminate. The Superbox was a ritual item — a domestic altar — that was not supposed to touch the walls and was never mass-produced.

“Throw your stuff in there and ... put it in the center of the room and psychically engage with it,” the curator said, adding: “This little box contained your afterlife needs, while this one contained your modern-life needs.” The same room boasts one of Donald Judd’s Minimalist stack sculptures (“Untitled,” 1968), whose verticality mirrors that of Sottsass’ boxes.

Sottsass was born in Innsbruck, Austria, in 1917 and studied architecture at a technical university in Turin, where his father maintained a studio and reverence for Otto Wagner, the father of Modernist architecture in Austria. As the curator framed it, Sottsass’ objects “have something of the rigor of the Germanic as well as the lyricism and the color of the Italian.”

He went to New York in 1956 and worked briefly for the industrial designer George Nelson before being recruited by Olivetti in 1957, an association that lasted 23 years. Sottsass kept his own studio in Milan and worked as an outside consultant for the company, which was located near Turin.

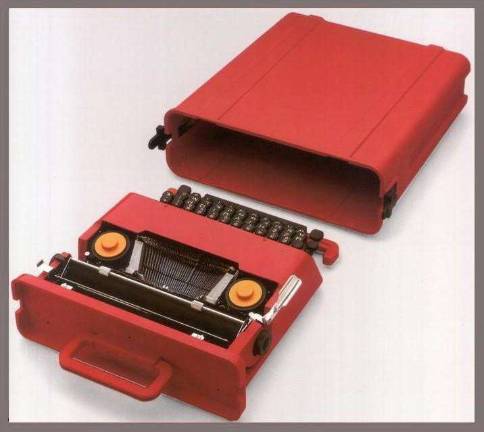

He famously designed Olivetti’s Elea 9003 (1959), the first all-transistor mainframe computer, and its lipstick-red manual typewriter, “Valentine” (1968), a portable machine with a plastic case and erotic-looking scroll caps in orange. The latter, a Pop Art-inspired icon, is widely seen as a forerunner of Apple’s rainbow-colored iMacs, introduced in 1998.

In 1961, Sottsass and his first wife traveled to India, a journey that had a lasting impact on his aesthetic. “Today we want uniqueness, we want individuality,” Larsen said, citing online retailer Etsy, which markets handmade and vintage items. “He’s the one who started that. He found his way of being individual and unique by going to India.”

The colors, the art, the architecture and the artifacts of the country made a profound impression. But it was a near-death experience in 1962 that was the catalyst for some of his most inventive pieces — the totems. They dramatically rise up on a platform in the center of a gallery filled with the designer’s small-scale ceramics and the non-European art they parallel.

Recovering from a rare form of nephritis at a hospital in California, Sottsass sketched a vertical stack, mimicking the medicine containers that filled his world. The drawing led to a series of 21 ceramic totems, first exhibited in Milan in 1967 under the title “Menhir, Ziggurat, Stupas, Hydrants & Gas Pumps,” a nod to the designer’s myriad sources of inspiration. Five works can be seen here, each with a spiritual or snarky socio-political message — e.g., “Large Carcinogenic Vase to Conserve State Cigarettes” (1964–67) and “Two Menhirs and a Large Phallus (To Introduce into Authority)” (1964-67).

But as Larsen explained, Sottsass’ real innovation boils down to color and pattern: “It’s about celebrating the skin — color and surface pattern. In plastic laminate or textile form, the patterns become the foundation for the palette for Memphis designers to pick and choose whatever they want.”

The emphasis on skin, he added, is “all about sensation, excitement, stimulation, memories — these are the functions [that matter],” a jab at modernism, which Sottsass ultimately rejected.

The Memphis pieces wow with their sheer audacity and playfulness. The “Carlton Room Divider” (1981), a collective classic, is a hybrid bookcase, chest and space divider that looks like it’s topped by a stick figure. Per the wall text: “It may be read variously as a robot greeting the user with open arms, a many armed Hindu goddess, or even a triumphant man atop a constructed chaos of his own making.”

Or not.