A Century Later, Mac Conner Has His Moment

Museum of the City of New York plays host through mid-January

Mac Conner is not a household name. Even Guest Curator Terrence Brown, former long-time director of the Society of Illustrators, "didn't know the name." But Conner (born in 1913) helped define the look of postwar America in scads of illustrations for mass-market magazines and advertisements in the late 1940s-1960s. He was, as the museum boasts, one of the original Mad Men. And now, he is getting his due in "Mac Conner: A New York Life," an impressive retrospective on view through January 19, 2015.

Some 70 original artworks, along with a wall map, photographs, tear sheets, pastel sketches, and some actual magazines, adorn the walls in this institution on Museum Mile devoted to celebrating influential New Yorkers and preserving the city's artistic and historical heritage. Conner, who lives on Fifth Avenue, came on the scene mid-century, when New York was the media capital of the world. Print magazines were ubiquitous. They "were your TVs, where you got your stories" before advertisers siphoned off dollars for television, according to Brown.

It was the heyday of women's magazines, and Conner rode the wave, accepting assignments from the "Seven Sisters"-including Redbook, McCall's, Ladies' Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, and Woman's Day-while at the same time serving clients at a constellation of Madison Avenue ad agencies.

Like his hero Norman Rockwell, whose magazine art he discovered while working in his father's general store, Conner's work made the cover of The Saturday Evening Post, a notable feat given that the editors initially rejected numerous pitches. Three such covers are on display, in addition to a map that pinpoints a selection of the more than 600 ad agencies and myriad magazine publishers and commercial art and photo studios clustered in Manhattan during this golden age of publishing.

A shy, small-town boy from New Jersey, Conner started out as a sign painter and took an art correspondence course, before studying at the Pennsylvania Museum School of Industrial Art and, later, New York's Grand Central School of Art. He came to the city during World War II, tasked with illustrating training materials for the Navy. He stayed on after the war and quickly befriended salesman Bill Neeley and artist Wilson Scruggs at Lawrence Studios on Lexington Avenue. The three founded Neeley Associates, a studio representing commercial artists, which eventually settled on West 45th Street, off 5th Avenue.

An entertaining video introduces the exhibit, with a dapper Conner, in blue blazer and pale-blue shirt, enthusing about his life's work. "You didn't make a lot of money, but you made some. I wasn't interested in that. I was interested in doing the painting. I loved to do it."

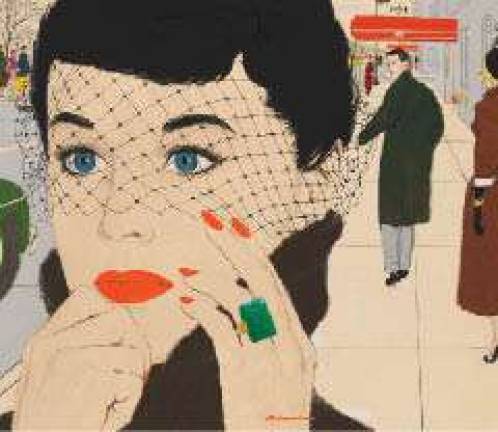

He derived the most pleasure from illustrating magazine fiction-short stories or serialized novels-work that was less rule-bound (but less lucrative) than producing illustrations for big-name advertisers. He is known especially for his sense of design, his unusual perspective, and his use of bold, flat colors, pattern, and detail.

The show lays out the themes of the stories he illustrated-Eisenhower-era family life, romance ("boy/girl"), rebellious youth ("juvenile delinquency"), noir crime and mystery-and gives a fascinating in-depth look at the collaborative process of producing the illustrations for the magazines.

But as one circles the show, it is hard not to appreciate just how accurately Conner mirrored the spirit of the age and had to cater to advertisers who were targeting a white, suburban, mostly Protestant audience in the years preceding the social movements of the 1960s. The images, with a few exceptions, depict a homogenous society. The women are tall, thin, in many cases blonde, with perfect nails, hair, make-up and accessories. They wear gloves and chic hats with veils. They are glamorous, idealized emblems of the period, like Betty in Mad Men and Libby in Masters of Sex.

When photographs increasingly supplanted hand-painted pictures in magazines and ads and women's publications de-emphasized fiction, Conner turned his talents to illustrating children's textbooks and the covers of romance novels. The show documents this transition, but it lavishes most of its attention on those early, heady days when New York was at the center of the magazine publishing world and print was king. As Conner, who considers himself a designer, not an artist, sums up his craft: "It was a way of speaking, a way to get your feelings out. It was a happy journey doing these paintings."