A west side story

Most Americans know that Harlem is the most influential African-American community in New York, and possibly the United States. But before World War I, the largest black community in New York lived in San Juan Hill.

San Juan Hill’s formal name was Lincoln Square, and its boundaries were roughly 59th Street, 65th Street, Amsterdam Avenue and West End Avenue. African-Americans began moving here in the late 19th century from Greenwich Village, where an earlier black community existed, and also, of course, from the South.

The name San Juan Hill refers to a battle in the Spanish-American War of 1898. Some say the neighborhood was called San Juan Hill because many African-American veterans of that war lived in the area. But others say the name came from the constant battles between African-American gangs from the neighborhood and Irish-American gangs from nearby.

The neighborhood also had another name: the Jungles. Indeed, an early jazz club in the area was called the Jungles Café. White jazz clarinetist Milton “Mezz” Mezzrow, who embraced the black aesthetic and moved to Harlem in the early 1930s, used the term in his autobiography, “Really the Blues.”

Mezzrow befriended two elderly men who lived in his Harlem tenement. “The only sport they remembered from when they were growing up in the Jungles was dropping bricks on cops’ heads from their windows,” he recalled. On another occasion, he was playing records by jazz pianists, when one of them displayed a record by James P. Johnson, put it on the turntable, and exclaimed, “Here’s a boy from the Jungles who makes all the other [piano players] look sick!”

According to historian Marcy Sacks’ “Before Harlem,” many black churches moved into the area in the 1880s and 1890s, among them St. Mark’s Methodist Episcopal, Mt. Olivet Baptist and St. Benedict the Moore. San Juan Hill also boasted numerous fraternal organizations, such as the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows, the Colored Freemasons and the Negro Elks.

Perhaps the most lasting legacy of San Juan Hill was its jazz musicians. The best-known were the aforementioned James P. Johnson and Thelonious Monk. Johnson, who first became active in the 1910s, pioneered the stride style of piano and wrote many famous jazz songs in the 1920s, such as the original “Charleston” and “If I Could Be With You One Hour Tonight.”

Monk, who grew up in the area in the 1920s and ‘30s, was an integral part of the bebop revolution of the 1940s, playing with such artists as Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Kenny Clarke and Miles Davis. He’s credited with originating the bebop “uniform” of a beret, glasses and a goatee.

The movement of African-Americans from San Juan Hill into Harlem started in the first decade of the 20th century and continued into the 1910s and 1920s. The relatively newer tenements of Harlem, most of them built for middle-class whites, had more light and air and more spacious rooms than the older tenements of San Juan Hill, which often had only one bathroom per floor and didn’t offer heat or hot water. (The Phipps Houses on West 63rd Street where Monk lived, built by philanthropist Henry Phipps as “model tenements,” were an exception.) Soon, new arrivals from the South headed directly to Harlem, not San Juan Hill.

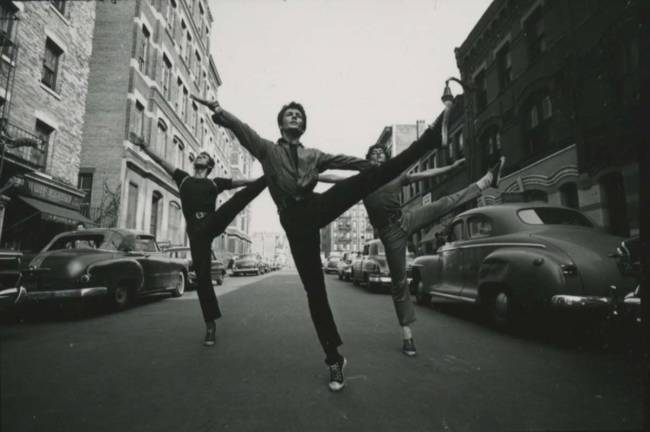

By the 1950s, San Juan Hill’s black population had dwindled and many Puerto Rican families moved in. The neighborhood was the “turf” of the fictional Sharks, a Puerto Rican gang, in “West Side Story,” and indeed, parts of the movie were shot there.

In 1940, the New York City Housing Authority called it “the worst slum district in New York City,” setting the stage for urban renewal. Part of the neighborhood was destroyed in 1947-48 to build the Housing Authority’s own Amsterdam Houses.

Then, in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, more than 1,500 families, mainly black and Puerto Rican, were displaced in order to make room for Lincoln Center. The “West Side Story” scenes were shot after the old buildings had already been condemned. And by the mid-1960s, except for a few scattered buildings — including the Phipps Houes — San Juan Hill was history.