tuning in on tin pan alley

BY RAANAN GEBERER

“Hey, Joe! I’m gonna have a new song in the Ziegfeld Follies. It’s guaranteed to be a hit!”

“Say, that ain’t nothin’! Al Jolson’s agreed to sing one of my songs in his new revue at the Winter Garden. When that guy gets down on one knee, the crowd’ll go wild!”

This imaginary exchange between two songwriters might have taken place a century or so ago on West 28th Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues — aka, Tin Pan Alley.

To understand Tin Pan Alley, we must understand the music industry in the 19th century, before the phonograph became popular. Aside from occasional trips to the theater, most music was made at home. Groups of friends getting together and playing the piano, the mandolin, the banjo and other instruments was a popular pastime. And to play, you needed sheet music.

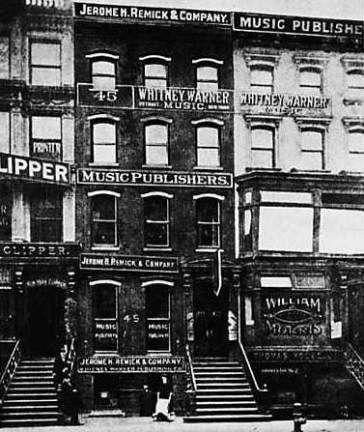

The sheet music industry received a big boost when Charles K. Harris’ song “After the Ball,” written in 1891, sold five million copies. Suddenly, everybody wanted to get into the music business. By 1900, that stretch of 28th Street was the capital of the music industry in the United States, populated by dozens of publishers, songwriters and associated folk.

There are several versions of how the street got the name “Tin Pan Alley,” but all agree that the name refers to the cacophonous sound of songwriters banging out tunes on their upright pianos all at once — like a bunch of people banging on tin pans.

Tin Pan Alley attracted a new breed of songwriter — a first-generation son of immigrants, especially although not exclusively Jewish immigrants. They turned out many types of songs. Love songs, of course, have always been popular. There were also nostalgia songs like “Swanee,” tributes to newfangled technology such as “In My Merry Oldsmobile,” patriotic songs like “You’re a Grand Old Flag” and novelties like “Yiddle on Your Fiddle, Play Me Some Ragtime.” Tin Pan Alley was also quick to embrace the new rhythms of ragtime, and later jazz.

Once a tune was published, “song pluggers” publicized it, trying to spur sales of sheet music and, increasingly, phonograph records. The pluggers played the songs at music stores, department stores and public events. They also tried to interest popular singers in the songs and get them placed in musical revues. Irving Berlin, George Gershwin and Harry Warren are said have got their start as song pluggers.

What happened to Tin Pan Alley? Music publishers began to move to the West 40s, closer to the emerging Broadway Theater District, as early as the end of the first decade of the 20th century. This movement accelerated during the 1910s and 1920s.

But also, the structure of the music business, and musical theater itself, changed. During the heyday of Tin Pan Alley, individual songs were placed haphazardly into revues. Of course there were exceptions, such as George M. Cohan’s blockbuster productions, but the emphasis was on revues.

The 1920s in particular saw the birth of the modern, integrated musical comedy. Now, composers were asked to write for an entire show, and it became commonplace to refer to “the new Rodgers and Hart show” or “the new Gershwin show.” Although songs still had to be published, the songwriter’s main contact was with the show’s producer. The Hollywood musical of the 1930s was an extension of this development.

The phrase “Tin Pan Alley” persisted for years after songwriters had moved out of West 28th Street. It came to mean the popular songwriting industry as a whole. These days, that stretch of 28th Street is populated by wholesale outlets peddling inexpensive clothing, jewelry and perfume. But whenever someone bangs out “Take Me Out to the Ball Game,” “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” or “Give My Regards to Broadway” on an upright piano, Tin Pan Alley’s spirit echoes.