Remembering That Day

Impressions from first responders seeing the 9/11 Memorial Museum for the first time

Retired NYPD detective Rose Colon hasn't been back to Ground Zero since September 11, 2001.

She was in Brooklyn when the first plane hit the North Tower at 8:46 a.m. She responded to the scene, and was injured after falling into a manhole while performing search and rescue operations with other first responders. Colon was evacuated before the first tower fell, and hasn't felt the need to come back.

"We actually retired after Sept. 11," said Colon, who returned to Ground Zero last week for the first time, to visit the newly opened 9/11 Memorial Museum with a friend, NYPD Sergeant Amy Loretoni, who also retired soon after the attacks.

Before opening to the public, the museum was open for a week to first responders and relatives of those who lost their lives. Our Town Downtown visited Ground Zero to speak with those who were granted advance access about their impressions of the museum and their recollections of that day.

Colon and Loretoni said for them, the most emotional exhibit was the Wall of Faces, which features photographs of the nearly 3,000 people who lost their lives that day and is meant to convey the scale of human loss. An adjoining chamber shows photographs, biographical information and audio recordings of individual victims from the day of the attack.

"It was very nice except that they didn't have a lot of information on the police," said Colon. "I mean we did lose a lot of cops and Port Authority police." Twenty-three NYPD officers and 37 Port Authority officers lost their lives on Sept. 11.

"If you were working that day and you were a cop, you can actually hear the cops dying. Everyone died equally, there was no color, there was no race, there was no religion in there," said Loretoni.

One of Colon's tasks in the aftermath of the attacks was to listen to and transcribe the 911 tapes of police officers who were trapped, and later died, after the towers fell. The officers, who knew all 911 calls are recorded, were saying farewell to their loved ones on the tapes.

As a result of her injury, Colon now lives with Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy, a disease causing chronic pain in the ankle she broke, as well as PTSD. Loretoni said she also suffers from PTSD as a result of being a first responder to the scene.

"It's not going to trigger in there," said Loretoni, gesturing to the museum. "Sometimes things don't trigger until later. You might be sitting at home and maybe they play one of those 9/11 songs they played during that period, and that will trigger the PTSD."

Four brothers

Bill Amaniera was an EMS technician and a first responder to Ground Zero on Sept. 11. He has three brothers in the NYPD, all of whom responded soon after him to the scene.

"I was the first one here, and they got here right after me. I was here before the towers actually came down," said Amaniera, whose one brother was in an NYPD marine unit driving police boats up and down the Hudson River. The Amaniera brothers all survived 9/11, though Amaniera's parents, as well as his two now-adult sons, waited hours to hear news from them.

"It brought back some rough times, but it also brought back some positive memories of buddies of mine that I lost," he said, of the museum. "I thought it was very respectful and tasteful."

In a notebook at the museum, where first responders could jot down thoughts as they toured the exhibits, Amaniera wrote that he, like many others, will never forget. "You know, they say 'Never forget,'" said Amaniera. "But the reality is, I will never forget."

Confusion, and concern for the future

Jim Larsen worked for the Port Authority on the 65th floor of the North Tower.

"I compacted the whole day into confusion, from the time I left to the time I started walking down the stairs, until I got home. I just kept moving, no panic," said Larsen, who lives about an hour north of Manhattan.

"Really the first time I noticed the smoke was at City Hall when we stopped, and that was when the second tower collapsed," said Larsen. "Another moment of confusion, the dust cloud was coming up Broadway."

Was it hard walking around the museum? "It was, in a way, but I get the impression that you have to have had some direct connection to the objects that are in the museum, otherwise I don't know if people would appreciate it as much."

Although Larsen was in the literal epicenter of the attacks, looking back he feels as though he was merely on the fringes.

"For me, I would say maybe I always felt guilty after that. I got home and I didn't have a spot of dust on me. I got wet, but that was from coming down the stairs when the sprinklers were on, but by the time I got home I was dry," he said. "I didn't see any blood, I didn't see anybody like what I saw in the pictures, walking through all covered in dust. Like I said, in a way I felt guilty about it. I dodged the grim reaper."

Larsen said his career has taken him all over the world, putting him in contact with many different cultures and perspectives. He remembers worrying how the United States would respond in the aftermath of Sept. 11.

"I was concerned with how the United States would react," he said. "I knew many Muslims, and they were good people. I was just concerned that a lot of good and innocent people would be hurt."

Utter disorientation

Pete Begley was a battalion commander in the FDNY and watched from home as the first plane slammed into the North Tower. He knew immediately that he had to get to Lower Manhattan. "I was off that day," he said, "but then again everybody came to work."

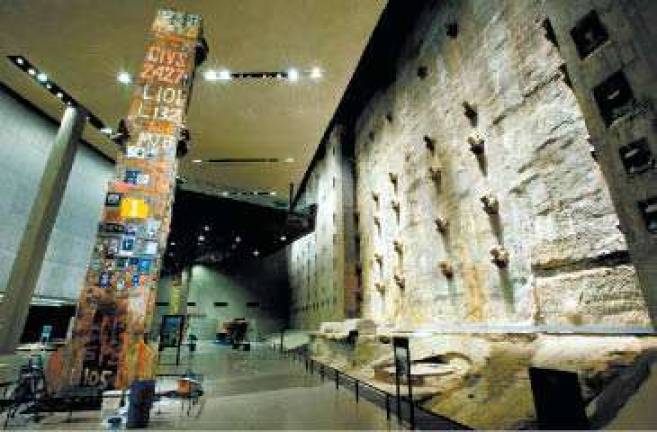

Begley said the scene was so disorienting that he couldn't even tell where the West Side Highway was located, or where the firehouse on Liberty Street was, a building that was very familiar to him.

"I worked in that place. And when I showed up down here in the rubble, after the towers fell, I couldn't get my bearings," he said. "I didn't know where I was because of the mounds, the steel, everything."

Begley, toured the museum with his wife, Gloria, and said portions of the museum were hard for him to take in.

"The thing of it was, the TV didn't do it justice. I saw the plane hit the tower at home, so I saw some devastation on TV, but by the time I got down here it was a whole different world. I couldn't describe it. You're like this small," he said, pinching his pointer finger and thumb to within an inch of each other. "You experienced a lot more devastation right here in the area, and I wish everybody could see that, but [the museum] is good enough."

Begley retired from the FDNY in 2002. "I was thinking about retiring but they asked people to stay so I stayed another year. I did 32 years, that was enough," he said.

The Begleys walked over to the reflecting pool, where tourists were pushing strollers and taking smiling photos in front of the names of the dead, 2,753 of which ring both pools where the towers once stood. Nearby, first responders trickled out of the museum in twos and threes, occasionally greeting an old face but mostly walking in silence.

Det. Rose Colon and Sgt. Amy Loretoni said they'd visit the museum again, perhaps bringing friends and loved ones next time. There's more to see, said Loretoni, but for today they'd had enough.

"In the museum, it's like you're trying to absorb as much information as you can and look at everything. I don't think we took enough time," she said.