Reporting By Drawing

In her 30 years as a courtroom sketch artist, Elizabeth Williams has witnessed and recorded many famous cases

Elizabeth Williams takes low-tech tools into a place where cameras and other recording devices aren't allowed ? federal courtrooms. With her brushes, pencils, pastels, paint and paper she re-creates scenes that would not normally be seen by the wider public.

In her 30-plus years of being a courtroom sketch artist she's covered the high profile cases of John DeLorean, Martha Stewart, John Gotti, Dominique Strauss-Kahn and the Times Square Bomber, among many others.

She recently teamed up with four other courtroom sketch artists to collaborate on a book of sketches spanning 50 years of high courtroom drama. The book is set to be released by CUNY Journalism Press in early-2014.

We spoke to Williams about her interesting work and how she always gets her picture no matter the circumstances.

How long have you been a courtroom sketch artist? Do you still find it interesting?

I started working as a court artist in Los Angeles in 1980. My first really big case though was the 1984 trial of John Delorean [the U.S. engineer and automobile maker who successfully defended himself against federal drug-trafficking charges in 1982. His DeLorean DMC-12 sports car was featured in the 1985 film Back to the Future.]

I find people interesting, so drawing in a courtroom is always interesting; also drawing in the subway and on the streets of NYC I find interesting. For several years, I have created paintings and drawings of NYC scenes for an art auction benefit for downtown's Manhattan Youth. I love doing that too. I find it all interesting.

How did you become a sketch artist? When did you know that's where you wanted your career to go?

I was working in Hollywood drawing illustrations for costume designers but that was not paying the bills and a teacher in one of my grad courses suggested I try court illustration.

It's not so much that I decided where my career would go, as the economy and the reality of the illustration business took me in this direction. Back in the 80s and 90s I was hired to do general illustration jobs and over the years, have illustrated books, magazines, advertising campaigns, pharmaceutical brochures, etc... But recently with the rise of Photoshop, the decline in art budgets and the proliferation of stock illustration there is not a lot of general illustration work out there. So court artwork is a major piece of my business now. The news business must still use us in federal courtrooms if editors feel it is important to show a specific scene or defendant; it is not a creative decision to hire us, it is a journalistic one. They would always rather have cameras but they can't in federal court.

How do you regard your role as a sketch artist in a journalistic sense?

We are first journalists and our job is to draw the courtroom scene as honestly as possible.

What's the craziest thing you've seen in the courtroom in your time as a sketch artist?

Two things come to mind, one was during the Yusef Hawkins verdict when the jury did not find the second defendant guilty of murder, the spectators and family went so nuts. That was the only time I felt was really in danger of getting hurt, but Al Sharpton was able to control the crowd and moved them outside to see their rage.

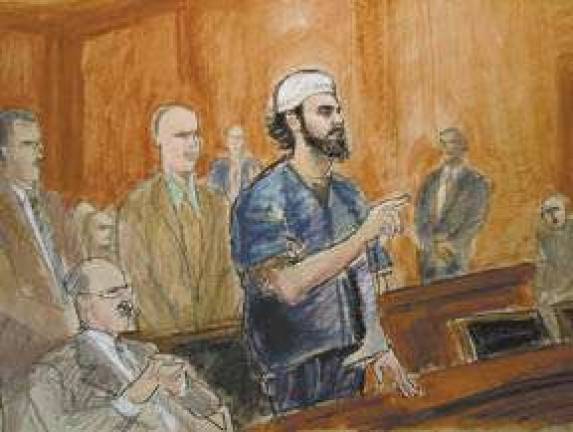

The other craziest thing is the recent terrorist, Abu Hamza - the handless terrorist. I've never seen that before, a defendant missing limbs, and from what I understand it was due to him trying to build a bomb.

What different skills does a courtroom sketch artist need to have over say a landscape artist?

You need nerves of steel, and cannot be thrown by anything. Our clients care about the end product, and you need to deliver it, and on time, no matter what the conditions. The subject may be in court for just minutes, your seat and view can be rotten, but you still have to get the scene. Landscape is a completely different type of artwork, and is based on a whole different set of standards. Trees and bushes don't move, the trees, bushes and fields don't get up and walk out.

Is there any one detail you always look for when making a sketch?

The most important issue is the likeness, the next is the scene; we are there in place of cameras, so that is our job.

Approximately how long does it take to make a sketch?

Depends what it is, if you're covering a long trial and a witness is on the stand all morning, you can draw two nicely finished illustrations during a morning session in court, i.e. three hours.

During an arraignment, where there is very limited time, and a pressing deadline, you take what they give you: 15 minutes or 20 minutes, it depends.

What sort of tools do you take into the courtroom to make your sketches? What's your process like?

I use brush pens, colored pencils, oil pastel and oil paint sticks; it is a technique I developed over the years.

I always wait to draw the main subject, everything else falls from that.

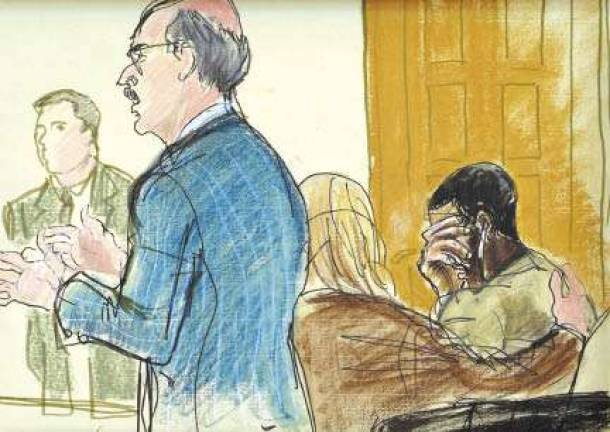

If a specific moment occurs I feel is important, then I whip out a piece of paper and quickly draw what I see. A good example of that was the Somali pirate [recently depicted in the film Captain Phillips with Tom Hanks]. He was sitting in court during his arraignment and all of a sudden, when his parents were mentioned by the judge, he broke down and wept. He had been smiling previously and one of the papers called him "Jolly Roger" but then once he got into court he cried. I had to draw that, and did. That drawing made the cover of the New York Post.

Do you ever just sketch the outlines of a scene and move on to another one because things are happening so fast? Do you take written notes on mood, emotion, to accompany your sketches?

This is a very good question, because you bring up the issue of things moving so fast.

What I do to combat that, is first, as soon as I can see my subject (usually a defendant) I will draw over and over very quickly the person's face, so I understand the shape and structure. Then I try, (and hope) to get something eventually I feel is close enough that I can expand from there. If something else happens, like the Somali pirate, I just whip out that other piece of paper and start drawing. Then once that scene is over, I will go back to the other beginning of the face or figure I felt was worthy enough to take to a finished state.

Has the rise of the internet and the changing news cycle affected your work process?

The issue is the deadlines, especially the rolling deadlines with wire services, they never stop and we are always racing against the clock. One is always caught in a delicate balance of determining the quality of the artwork versus the amount of time, when is good "good enough." All clients would like the art as soon as possible, yet they want it looking good and spot-on right. So we are constantly challenged with that issue.

What can you tell me about the book that's about to be released?

The book is a compilation of artwork by five artists who have covered famous court cases from around the country over the last 50 years. Cases include Jack Ruby [who killed President John F. Kennedy's assassin Lee Harvey Oswald in the basement of a Dallas police station], mob kingpin John Gotti, the Watergate burglars, key Iran-Contra players, Charles Manson, David "Son of Sam" Berkowitz, members of the Black Panther party, kidnapped heiress Patty Hearst, pop icon Michael Jackson, Mohammed Salameh, the terrorist behind the 1993 attack on the World Trade Center, and many more.

The book is being published by CUNY Journalism Press, a new academic imprint. The book's main format is an illustrated eBook, which is a relatively new type of illustrated book. The book's website is www.illustratedcourtroom.com and the Facebook at Illustrated Courtroom.

Where has your work been featured?

My work was recently featured in the Wall Street Journal, CNBC News, Bloomberg TV, Art and Auction magazine, WABC news and via the Associated Press my work has been in the Los Angeles Times, The Christian Science Monitor, The New York Times, USA today, London Times, The NY Daily News and The Daily Beast.

When I work for the AP, sometimes my work can be sent across the globe and end up in all sorts of places from Canada, the United Kingdom, Europe, Argentina and Russia - it just depends upon the story. Several big global stories I have covered were: the Russian Spies, Osama Bin Ladin's son-in-law, Al Libi (the terrorist captured in Libya), the case of Argentina's bonds defaulting and Dominique Strauss-Kahn.