See the World Through Max Weinman's Lens

There are no explosions in Max Weinman's films. There is no sex, except perhaps a sudden caught breath in a forest scene, which subconsciously represents the first flicker of lust. There's no cursing. No drugs. Very few people. Talking. Sound. And with those qualities stripped we're left with a beautiful commentary on wanderlust and an open world unavailable past the skyline horizon.

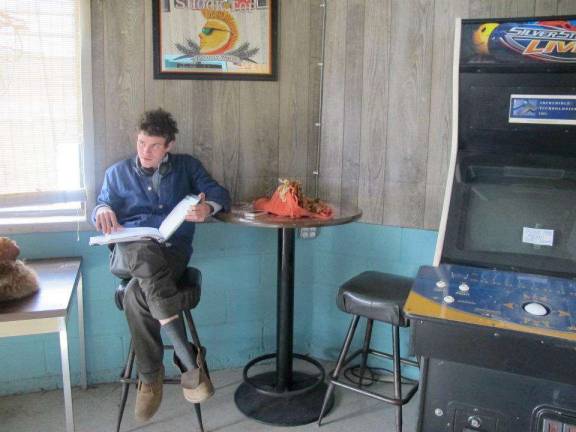

Weinman grew up in downtown Manhattan, and summered in France. He has a laidback disposition and his natural facial expression is a comfortable smile. He started shooting films in high school, unable to fully express and capture his surroundings in writing.Indeed, his films seem synonymous to a stream of consciousness. His films North South and Portiragnes are travelogues, the former about a road trip across the US where he found untouched America not in the body of a woman, but the lay of the land. The latter, a film that speaks to his summers abroad. His latest film Apsis, makes impressive use of light as a story modifier, and has shifty moments of panicked screaming and general unease.

There's a drastic shift between the film Apsis and all of your other shorts. There's narrative, backing sound, it's completely black and white? What inspired that film? Where did it come from? It's true that my narrative shares very little in common with the lyrical films. The process is different. In my lyricalfilmmakingI'm taking from the world, and then through the editing, exploring ideas that have personal relevance. So, creating an internal narrative with the external. My narrative approach has been to create a world I don't live in, that is motivated and constructed by internal conflicts. The decision to make a narrative or a lyrical film really depends on the idea too. I don't think the ideas explored in Apsis would have been suitable for an observational film.

What exactly were the ideas? The film itself is beautiful and has forward momentum, but I had trouble digging up the subtext. I guess off the bat it's a story about a devilish man who's alone in a landscape. The film has gone through many changes in the course of its production, and it continues to take on new meanings and interpretations now that I've begun showing it around. A friend called it a creation story, and likened it to the myth of Uranus and Gaia. I did a lot of research on the occult in the beginning of pre-production, to get some ideas flowing. There are elements taken from that research, namely the idea of the Incubus, the male incarnation of the nightmare that stalks females in their sleep. There are also strong themes of the masculine and the feminine, the battle between the two, in this character.

What was the production of the film like? Well we shot it in the South. There were four in the crew including myself: the cinematographer, Jake Magee, whom I collaborate with frequently and who co-founded my production company, Autoscopy Films; then my actors James Reid and Hannah Rikoon. The four of us went to the desert for five days, and then finished shooting five months later in a studio at Bard College. We thought we had finished shooting after the desert, but when I got the footage back it felt so bare, so I took five months to figure out the missing pieces. I'm lucky to have found people as creative and dedicated as those guys, film is so collaborative, the crew is essential.

There's a prolonged gaze to your films that enhances the idea that we are getting a look into how you see the world. The story of a lot of the films seems to be how one person's view is totally unique. How do you see your vision as part of your stories? Feeling the perspective of the camera is important to my films, however I think the struggle in the editing is to reconsider the personal footage as symbols, to make it less personal and more accessible. For example, the shots of my family in Portiragnes aren't given any context, so the viewer doesn't immediately know my connection to the people. Through the editing I try to evoke that intimacy.

With those glimpses we begin to see a life. What initially made you to pick up a camera? My filmmaking came out of my failed diary writing. I was writing all throughout high school, and filming as well-documenting my everyday life, just observing my surroundings. Both the writing and the filming were without catharsis. They were documentation without reflection and felt flat and unimportant. The editing is the writing, the reflection, and where the footage is given purpose.

Silence and stillness are important aspects of your work. What are you trying to say in using both? The film North South is silent because there was nothing to be evoked through sound. It's simply a voyage across America and back, and the shifts in the imagery are where the tension lies. Portiragnes uses an aggressive soundscape, because I wanted to emphasize the emotional subtext of the images, which is more anxious at times. Another reason North South is silent is so I can talk through it. My former professor, Peter Hutton, shows his breath-taking silent films to his class and gives a verbal context to his imagery, which makes the experience intimate and personal. These explanations are sure to change with every screening, but that's a part of it.

There's a really beautiful moment in the short film Portiragnes, where you're filming a close up of a young man hanging by the beach, and you slowly pan down and we see that he's picking at a scab on his knee. Are these moments directed or do you let them come naturally? I generally let things happen, but I will sometimes ask people to repeat actions. It really depends on the situation. In the case of Turner scratching his knee--Turner the young man and my best friend since birth--I saw him doing it, and asked him to keep scratching. Another scene in the film, where people are jumping off cliffs, they wanted me to film them doing back flips and the feeling was mutual. I shot Portiragnes in the summer and winter, and when I went back in the winter I had this idea of creating a narrative of a boy with his dog, and interweaving it with more lyrical shots I had from the summer, so there are some scenes that are loosely scripted.

What's the role of the travelogue filmmaker in a generation that is constantly moving onto new things? I don't know what the role is, but I know that the technology available for filmmakers today lends itself to the ADD generation. The DSLRs are great cameras, don't get me wrong, but I fear people rely on the technology to make the image for them. They've created the aesthetic of our generation: the shaky shallow focus handheld camera, and it's purely because of those 35mm lenses. This type of instant gratification--the high resolution and easy workflow--fits in with our generation's approach to art making. I think we want things to come quick and be easy, but I guess I can't speak for everyone. I'm guilty of it too, don't get me wrong. My next project will be much longer, and I'm going to continue working in the 16mm format until they discontinue it. Knowing every shot is costing you moolah makes you slow down and really consider what you're doing, and that's been crucial for me.

What can you tell us about the duck hunting documentary you're working on? My very good friend slash film colleague, Dave McNeeley, grew up duck hunting so the subject is close to home for him, and he approached me about making a documentary about duck hunters. I was immediately interested in the idea because I wanted to, and still want to, shift my focus from the immediately personal to more anthropological subjects. A documentary where the camera's perspective is felt, but not directly attached. The film follows the duck hunters at first, then leaves them to focus on the space. There are similar tensions in hunting as there are in filmmaking: the waiting, watching, listening, we approached it with an awareness to the medium, but also with a sincere appreciation for the ritual, and the marsh.

Portiragnes from Max Weinman on Vimeo.